译者 | 卢鑫旺

51CTO读者成长计划社群招募,咨询小助手(微信号:CTOjishuzhan)

不久前,我们的一个核心Python库出现了性能问题。

这个特殊的库构成了我们3D数据处理管道的主要组件。这是一个相当大而复杂的库,它使用了NumPy和其他科学计算相关的Python包来进行大量的数学和几何运算。

我们的系统还必须在CPU资源有限的前提下工作,虽然一开始它表现得很好,但随着并发用户数量的增长,我们开始遇到问题,系统难以跟上负载。

我们得出的结论是,我们必须让我们的系统至少快50倍来处理增加的工作负载,我们认为Rust可以帮助我们实现这一目标。

因为我们遇到的性能问题很常见,所以我们可以在这篇(不太短的)文章中复现并解决它们。

所以,喝杯茶(或咖啡),我会带你了解

- 性能问题背后的潜在问题

- 可以解决这个问题的一些优化迭代

如果你想直接跳到最终代码,只需要快进到摘要部分即可。

1、运行示例

我们写一个小库,来展示我们最初的性能问题(完全是任意的一个示例)。

想象你有一个多边形列表和一个点列表,都是二维的。出于业务原因,我们希望将每个点“匹配”到一个多边形。

我们想像中的库将会是这样:

- 从点和多边形(都是2D)的初始化列表开始。

- 对于每个点,根据到中心的距离,找到一个更小的最接近它的多边形子集。

- 从这些多边形中,选择“最佳”的一个(我们将使用“最小面积”作为“最佳”)。

代码基本是这样:

from typing import List, Tuple

import numpy as np

from dataclasses import dataclass

from functools import cached_property

Point = np.array

@dataclass

class Polygon:

x: np.array

y: np.array

@cached_property

def center(self) -> Point: ...

def area(self) -> float: ...

def find_close_polygons(polygon_subset: List[Polygon], point: Point, max_dist: float) -> List[Polygon]:

...

def select_best_polygon(polygon_sets: List[Tuple[Point, List[Polygon]]]) -> List[Tuple[Point, Polygon]]:

...

def main(polygons: List[Polygon], points: np.ndarray) -> List[Tuple[Point, Polygon]]:

...关键的困难(性能方面)是Python对象和numpy数组的混合。

让我们对此做深入分析。

值得注意的是,对于这个玩具库来说,将部分/所有内容转换为向量化numpy可能是可行的,但对于真正的库来说,这几乎是不可能的,因为这会使代码的可读性和可修改性大大降低,并且收益有限(这里是一个部分向量化的版本,它更快,但与我们将要实现的结果还很远)。

此外,使用任何基于JIT的技巧(PyPy / numba)都只能带来非常小的收益(为了确保我们将进行测量)。

2、为什么不直接全部用Rust重写?

虽然完全重写很有吸引力,但它有几个问题:

库已经使用numpy进行了大量的计算,所以我们为什么要期望Rust更好呢?它很大并且复杂,有非常重的业务和高度集成的算法,重写将需要几个月的工作量,而我们有限的服务器资源已经快撑不住了。

一群友好的研究人员正在积极地研究这个库,来实现更好的算法,并做了大量的实验。不过,他们不是很乐意学习一种新的编程语言,等待程序编译并与借用检查器进行斗争。他们会感激我们没有用Rust完全替代这些Python代码实现的工作。

3、进入主题

介绍一下我们的好朋友profiler工具。

Python有一个内置的profiler分析器(cProfiler),但是对于这次的工作它并不是一个合适的工具:

- 它将为所有Python代码引入大量开销,而对本地代码不引入任何开销,因此我们的结果可能有偏差。

- 无法看到本地调用堆栈数据,这意味着我们将无法深入到Rust代码。

本次我们使用py-spy库,py-spy是一个采样性能分析工具,可以深入查看本地调用堆栈。

他们还慷慨地将预先构建的包发布到pypi,这样我们就可以通过下面的命令安装py-spy。

pip install py-spy并开始工作。

我们还需要一些衡量标准。

# measure.py

import time

import poly_match

import os

# Reduce noise, actually improve perf in our case.

os.environ["OPENBLAS_NUM_THREADS"] = "1"

polygons, points = poly_match.generate_example()

# We are going to increase this as the code gets faster and faster.

NUM_ITER = 10

t0 = time.perf_counter()

for _ in range(NUM_ITER):

poly_match.main(polygons, points)

t1 = time.perf_counter()

took = (t1 - t0) / NUM_ITER

print(f"Took and avg of {took * 1000:.2f}ms per iteration")这不是很科学,但它会让我们走得更远。

“好的基准测试很难。不要过于强调拥有完美的基准测试设置,尤其是当你开始优化一个程序时。”

—— ——Nicholas Nethercote 《高性能 Rust》

通过运行这个脚本,我们得到一些基础数据。

$ python measure.py

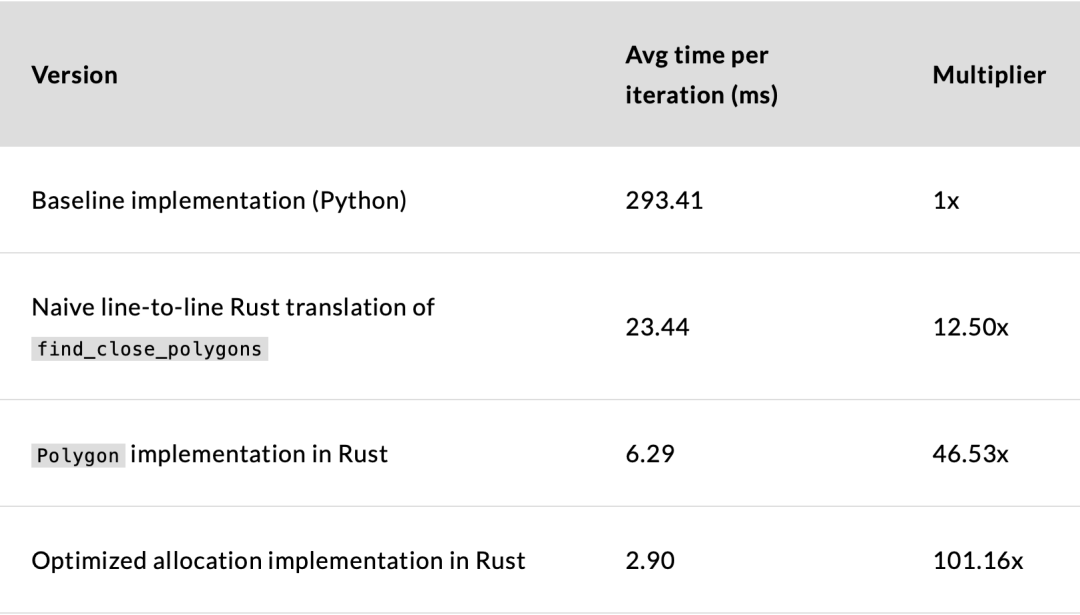

Took an avg of 293.41ms per iteration对于原始库,我们使用了50个不同的示例,以确保涵盖了所有情况。

这与整个系统性能相匹配,这意味着我们可以开始努力打破这个数字。

注意:我们还可以使用PyPy进行度量(我们还将添加一个预热,以允许JIT发挥它的魔力)。

$ conda create -n pypyenv -c conda-forge pypy numpy && conda activate pypyenv

$ pypy measure_with_warmup.py

Took an avg of 1495.81ms per iteration4、测量先行

让我们来看看这里有什么慢的地方。

$ py-spy record --native -o profile.svg -- python measure.py

py-spy> Sampling process 100 times a second. Press Control-C to exit.

Took an avg of 365.43ms per iteration

py-spy> Stopped sampling because process exited

py-spy> Wrote flamegraph data to 'profile.svg'. Samples: 391 Errors: 0可以看到这个工具引入的开销非常小,为了比较,我们使用cProfile的结果如下:

$ python -m cProfile measure.py

Took an avg of 546.47ms per iteration

7551778 function calls (7409483 primitive calls) in 7.806 seconds

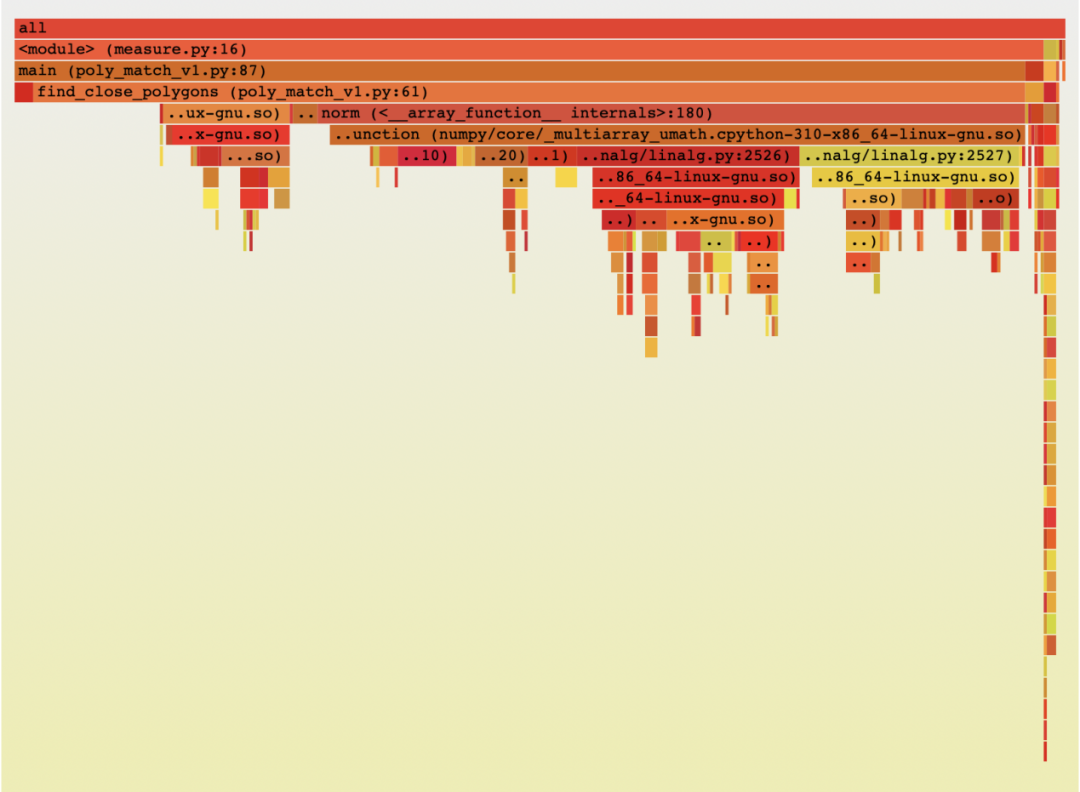

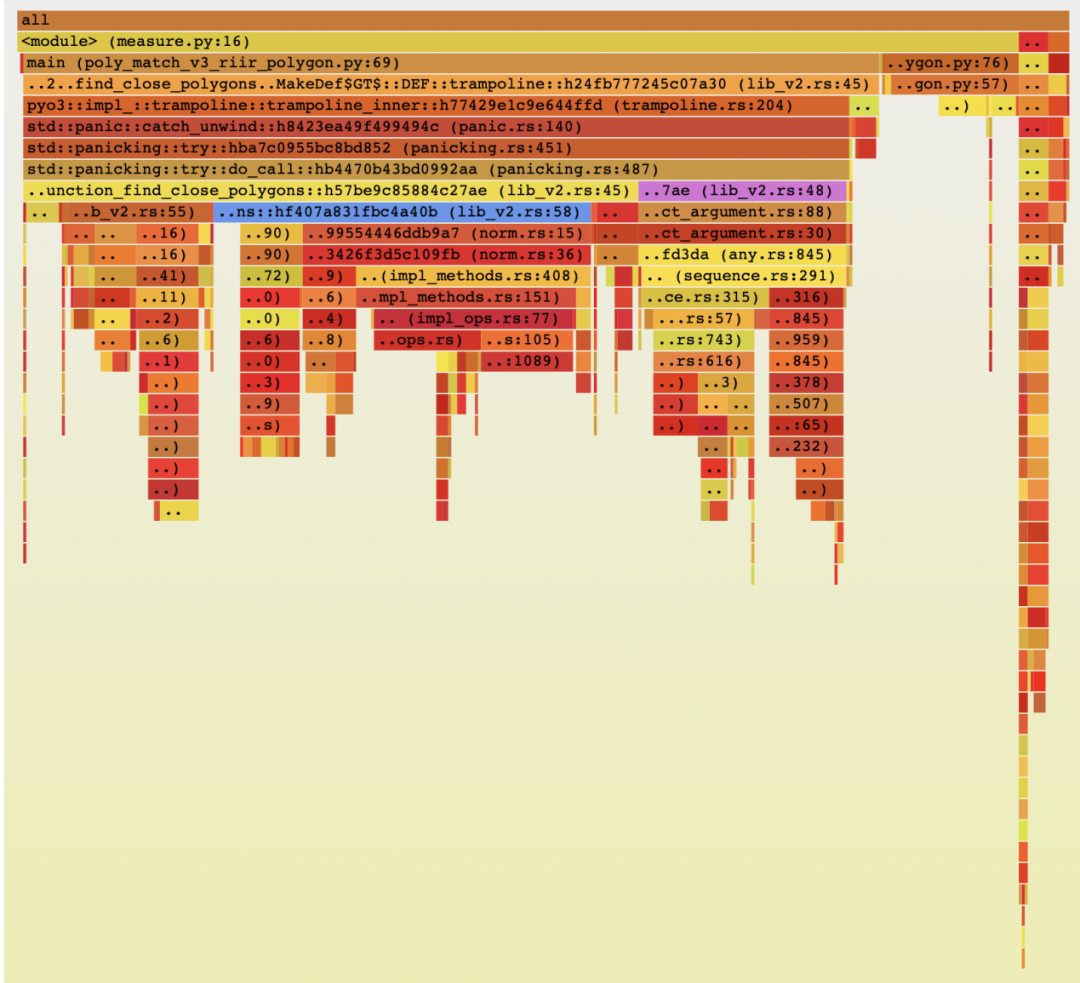

...我们得到了一个漂亮的红色图,称为火焰图:

每个框都是一个函数,我们可以看到我们在每个函数中花费的相对时间,包括它正在调用的函数(沿着图/堆栈向下)。试着点击一个标准框来放大它。

图中的主要结论如下:

- 绝大多数时间都花在find_close_polygons中。

- 大部分时间都花在代数计算上,这是一个numpy函数。

因此,让我们看一看find_close_polygons这个函数:

def find_close_polygons(

polygon_subset: List[Polygon], point: np.array, max_dist: float

) -> List[Polygon]:

close_polygons = []

for poly in polygon_subset:

if np.linalg.norm(poly.center - point) < max_dist:

close_polygons.append(poly)

return close_polygons我们打算用Rust来重写这个函数。

在深入探讨细节之前,有以下几点需要注意:

- 这个函数的入参和出参都是比较复杂的对象(Polygon类型的numpy.array数组)。

- 对象的大小很重要,拷贝这些对象会带来成本开销。

- 这个函数会被大量调用,因此我们必须考虑到自己引入的开销带来的影响。

5、我的第一个Rust模块

pyo3是一个用于Python和Rust之间交互的包。它有非常友好的文档,在这里说明了基本设置(https://pyo3.rs/v0.18.1/#using-rust-from-python)。

mkdir poly_match_rs && cd "$_"

pip install maturin

maturin init --bindings pyo3

maturin develop我们将要调用自己的poly_math_rs文件,然后添加一个叫find_close_polygons的函数。

一开始,大概会是这样:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

#[pyfunction]

fn find_close_polygons() -> PyResult<()> {

Ok(())

}

#[pymodule]

fn poly_match_rs(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(find_close_polygons, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}我们要记得在每次更新Rust库时执行maturin develop。

这样我们就可以调用我们的新函数了。

>>> poly_match_rs.find_close_polygons(polygons, point, max_dist)

E TypeError: poly_match_rs.poly_match_rs.find_close_polygons() takes no arguments (3 given)6、V1版:简单粗暴的使用Rust翻译代码

我们从匹配预期的API开始。

PyO3在Python到Rust的转换非常智能,所以非常容易:

#[pyfunction]

fn find_close_polygons(polygons: Vec<PyObject>, point: PyObject, max_dist: f64) -> PyResult<Vec<PyObject>> {

Ok(vec![])

}PyObject(顾名思义)是一个通用的“任意一个”Python对象。我们稍后会尝试与它交互。

这回让程序运行起来(尽管有错误)。

我只打算拷贝和粘贴原始的Python函数,并修复语法问题。

#[pyfunction]

fn find_close_polygons(polygons: Vec<PyObject>, point: PyObject, max_dist: f64) -> PyResult<Vec<PyObject>> {

let mut close_polygons = vec![];

for poly in polygons {

if norm(poly.center - point) < max_dist {

close_polygons.push(poly)

}

}

Ok(close_polygons)

}很不错,不过出现了编译错误:

% maturin develop

...

error[E0609]: no field `center` on type `Py<PyAny>`

--> src/lib.rs:8:22

|

8 | if norm(poly.center - point) < max_dist {

| ^^^^^^ unknown field

error[E0425]: cannot find function `norm` in this scope

--> src/lib.rs:8:12

|

8 | if norm(poly.center - point) < max_dist {

| ^^^^ not found in this scope

error: aborting due to 2 previous errors ] 58/59: poly_match_rs我们需要三个中间文件来实现我们的功能:

# For Rust-native array operations.

ndarray = "0.15"

# For a `norm` function for arrays.

ndarray-linalg = "0.16"

# For accessing numpy-created objects, based on `ndarray`.

numpy = "0.18"首先,让我们将不透明和通用的点:PyObject变成我们可以使用的对象。

就像我们向PyO3请求“Vec of PyObjects”一样,我们可以请求一个numpy数组,它会为我们自动转换参数。

use numpy::PyReadonlyArray1;

#[pyfunction]

fn find_close_polygons(

// An object which says "I have the GIL", so we can access Python-managed memory.

py: Python<'_>,

polygons: Vec<PyObject>,

// A reference to a numpy array we will be able to access.

point: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>,

max_dist: f64,

) -> PyResult<Vec<PyObject>> {

// Convert to `ndarray::ArrayView1`, a fully operational native array.

let point = point.as_array();

...

}由于point已经成为了ArrayView1,因此我们可以使用它了。比如:

/// Make the `norm` function available.

use ndarray_linalg::Norm;

assert_eq!((point.to_owned() - point).norm(), 0.); // Make the `norm` function available.现在,我们只需要获取每个多边形的中心,并将其“投射”到ArrayView1中。

在PyO3中看起来是这样:

let center = poly

.getattr(py, "center")? // Python-style getattr, requires a GIL token (`py`).

.extract::<PyReadonlyArray1<f64>>(py)? // Tell PyO3 what to convert the result to.

.as_array() // Like `point` before.

.to_owned(); // We need one of the sides of the `-` to be "owned".这有点晦涩难懂,但总的来说,结果是对原始代码进行了相当清晰的逐行翻译。

use pyo3::prelude::*;

use ndarray_linalg::Norm;

use numpy::PyReadonlyArray1;

#[pyfunction]

fn find_close_polygons(

py: Python<'_>,

polygons: Vec<PyObject>,

point: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>,

max_dist: f64,

) -> PyResult<Vec<PyObject>> {

let mut close_polygons = vec![];

let point = point.as_array();

for poly in polygons {

let center = poly

.getattr(py, "center")?

.extract::<PyReadonlyArray1<f64>>(py)?

.as_array()

.to_owned();

if (center - point).norm() < max_dist {

close_polygons.push(poly)

}

}

Ok(close_polygons)

}与原来的Python代码对比:

1.def find_close_polygons(

2. polygon_subset: List[Polygon], point: np.array, max_dist: float

3.) -> List[Polygon]:

4. close_polygons = []

5. for poly in polygon_subset:

6. if np.linalg.norm(poly.center - point) < max_dist:

7. close_polygons.append(poly)

8.

9. return close_polygons我们期待这个版本可以相对于原始的Python版本会有一些优势,实际情况是:

1.$ (cd ./poly_match_rs/ && maturin develop)

2.$ python measure.py

3.Took an avg of 609.46ms per iteration所以使用了Rust只是会更慢吗?我们只是忘了要提升速度,如果我们执行

maturn develop –release,我们可以得到更好的结果:

$ (cd ./poly_match_rs/ && maturin develop --release)

$ python measure.py

Took an avg of 23.44ms per iteration现在已经有了比较明显的加速!

我们还想了解我们的本地代码运行时的堆栈调用情况,所以我们将在发布时启用调试符号。这样我们不妨以最高速度运行。

1.# added to Cargo.toml

2.[profile.release]

3.debug = true # Debug symbols for our profiler.

4.lto = true # Link-time optimization.

5.codegen-units = 1 # Slower compilation but faster code.7、V2版- 使用Rust重写更多内容

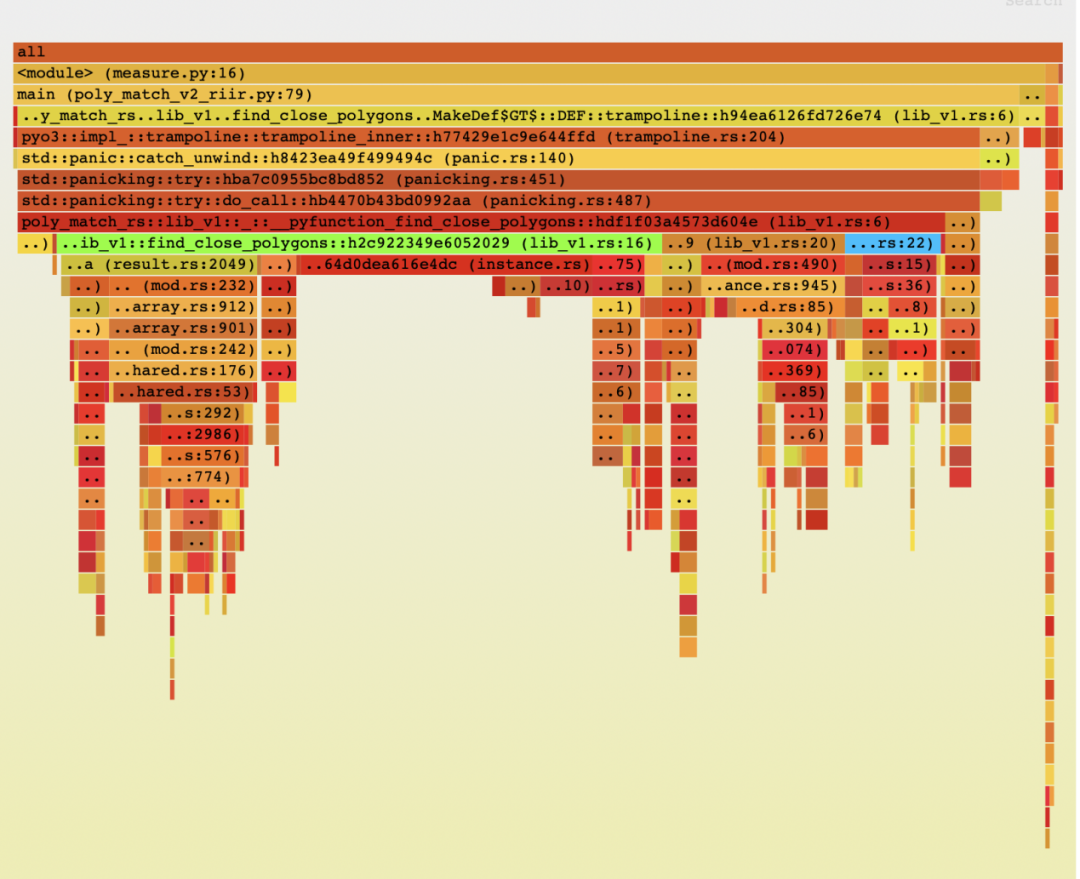

在py-spy使用--native标识能同时给我们展示python和新的本地代码。

再次执行py-spy

$ py-spy record --native -o profile.svg -- python measure.py

py-spy> Sampling process 100 times a second. Press Control-C to exit.左右滑动查看完整代码

我们得到了如下火焰图(添加了非红色,这样我们就可区分以参考它们):

根据本次输出的结果,我们发现了几个有意思的事情:

(1)我们可以看到find_close_polygons::... ::trampoline(Python直接调用)和__pyfunction_find_close_polyons(我们的实际实现)的相对大小,它们是95%对88%的样本,所以开销很小。

(2)lib_v1.rs:22(右边一个非常小的框)中展示的真正的处理逻辑 (if (center - point).norm() < max_dist {…})只占了整个运行时的约9%。所以10倍提升还是有可能的。

(3)大部分时间花销在lib_v1.rs:16,即poly.getattr(…).extract(…),如果我们放大可以看到具体的费时操作是getattr函数以及使用as_array获取底层数组。

这里的结论是,我们需要专注于解决第三点,而实现这一点的方法是在Rust中重写Polygon这个类。

首先,看一下原始Python代码:

@dataclass

class Polygon:

x: np.array

y: np.array

_area: float = None

@cached_property

def center(self) -> np.array:

centroid = np.array([self.x, self.y]).mean(axis=1)

return centroid

def area(self) -> float:

if self._area is None:

self._area = 0.5 * np.abs(

np.dot(self.x, np.roll(self.y, 1)) - np.dot(self.y, np.roll(self.x, 1))

)

return self._area我们希望尽可能多地保留现有的API,但目前我们并不需要把area方法变得更快。

真正的类可能具有额外复杂的内容,比如merge方法使用了scipy.spatial中的ConvexHull方法。

为了减少开销(并限制在这篇已经很长的文章的范围内),我们只会将Polygon类的核心功能用Rust实现,然后以Python子类的形式去实现API的其余部分。

我们的结构体struct是这样的:

// `Array1` is a 1d array, and the `numpy` crate will play nicely with it.

use ndarray::Array1;

// `subclass` tells PyO3 to allow subclassing this in Python.

#[pyclass(subclass)]

struct Polygon {

x: Array1<f64>,

y: Array1<f64>,

center: Array1<f64>,

}现在,我们需要真正的来实现它,我们想暴露poly.{x, y,center}作为:

(1)属性

(2)Numpy Array数组

我们还需要一个构造函数,以便Python可以创建新的Polygon类。

use numpy::{PyArray1, PyReadonlyArray1, ToPyArray};

#[pymethods]

impl Polygon {

#[new]

fn new(x: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>, y: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>) -> Polygon {

let x = x.as_array();

let y = y.as_array();

let center = Array1::from_vec(vec![x.mean().unwrap(), y.mean().unwrap()]);

Polygon {

x: x.to_owned(),

y: y.to_owned(),

center,

}

}

// the `Py<..>` in the return type is a way of saying "an Object owned by Python".

#[getter]

fn x(&self, py: Python<'_>) -> PyResult<Py<PyArray1<f64>>> {

Ok(self.x.to_pyarray(py).to_owned()) // Create a Python-owned, numpy version of `x`.

}

// Same for `y` and `center`.

}我们需要向模块中添加新的结构体作为一个类:

#[pymodule]

fn poly_match_rs(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_class::<Polygon>()?; // new.

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(find_close_polygons, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}然后,我们就可以更新Python代码来使用这个类:

class Polygon(poly_match_rs.Polygon):

_area: float = None

def area(self) -> float:

...编译之后成功运行,但是速度却慢了很多(x、y和center现在需要在每次访问时创建一个新的numpy数组)。

为了能真正提高性能,我们需要从Python实现的Polygon类中提取出原始的基于Rust实现的Polygon类。

PyO3能非常灵活的实现这种类型的操作,所以我们有几种方法可以做到这一点。但有一个限制是,我们还需要返回Python的Polygon类,并且我们不想对实际数据做任何的拷贝。

在每个PyObject对象上手动调用 .extract::<Polygon>(py)?是可以的,但是我们想让PyO3直接给我们Python实现的Polygon类。

这是Python所拥有的对象的引用,我们希望该对象包含一个原生Python类结构体的实例或者是它的子类。

#[pyfunction]

fn find_close_polygons(

py: Python<'_>,

polygons: Vec<Py<Polygon>>, // References to Python-owned objects.

point: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>,

max_dist: f64,

) -> PyResult<Vec<Py<Polygon>>> { // Return the same `Py` references, unmodified.

let mut close_polygons = vec![];

let point = point.as_array();

for poly in polygons {

let center = poly.borrow(py).center // Need to use the GIL (`py`) to borrow the underlying `Polygon`.

.to_owned();

if (center - point).norm() < max_dist {

close_polygons.push(poly)

}

}

Ok(close_polygons)

}看一下这次改进后的效果:

$ python measure.py

Took an avg of 6.29ms per iteration已经很接近目标了!

8、V3版:优化内存分配

让我们再看一下profiler的结果。

我们可以看到select_best_polygon方法在获取x 和y向量时调用了Rust的代码。我们可以解决这个问题,但这是一个非常小的潜在改进(可能只是10%的性能提升)。

可以看到有约20%的时间用在了extract_argument方法上(在lib_v2.rs:48的下方),这块仍是一个较大的开销。不过大部分时间还是消耗在PyIterator::next和PyTypeInfo::is_type_of上,这个并不容易去修复和提升。

很多时间花在了分配变量上。在lib_v2.rs:58中,我们可以看drop_in_place和to_owned。实际的线路大约占总时间的35%,这比我们预期的要多得多:这应该是所有数据都准备好的“快速位”。

让我们来解决最后一点。

这是我们有问题的片段:

let center = poly.borrow(py).center

.to_owned();

if (center - point).norm() < max_dist { ... }我们想要的是避免to_owned。但我们需要一个拥有的对象作为norm,所以我们必须手动实现。(我们之所以可以改进ndarray,是因为我们知道它实际上只是两个float32类型的数值)。

这看起来是这样的:

use ndarray_linalg::Scalar;

let center = &poly.as_ref(py).borrow().center;

if ((center[0] - point[0]).square() + (center[1] - point[1]).square()).sqrt() < max_dist {

close_polygons.push(poly)

}不过,Rust的借用检查器报错了:

error[E0505]: cannot move out of `poly` because it is borrowed

--> src/lib.rs:58:33

|

55 | let center = &poly.as_ref(py).borrow().center;

| ------------------------

| |

| borrow of `poly` occurs here

| a temporary with access to the borrow is created here ...

...

58 | close_polygons.push(poly);

| ^^^^ move out of `poly` occurs here

59 | }

60 | }

| - ... and the borrow might be used here, when that temporary is dropped and runs the `Drop` code for type `PyRef`借用检查器是对的,我们的代码有内存错误。

简单的修复方式是使用拷贝,然后编译close_ploygons.push(poly.clone())。

这种拷贝方式几乎不会带来额外性能开销,因为我们只是增加Python对象的引用计数。

然而,在这种情况下,我们也可以通过经典的Rust技巧来减少借用:

let norm = {

let center = &poly.as_ref(py).borrow().center;

((center[0] - point[0]).square() + (center[1] - point[1]).square()).sqrt()

};

if norm < max_dist {

close_polygons.push(poly)

}因为poly只在内部范围内借用,所以一旦我们执行到close_polygons.push,编译器就可以知道我们不再持有该引用,并正常编译新版本。

最终的结果是:

$ python measure.py

Took an avg of 2.90ms per iteration比之前的代码速度提升了100倍。

9、总结

我们从如下python代码开始

@dataclass

class Polygon:

x: np.array

y: np.array

_area: float = None

@cached_property

def center(self) -> np.array:

centroid = np.array([self.x, self.y]).mean(axis=1)

return centroid

def area(self) -> float:

...

def find_close_polygons(

polygon_subset: List[Polygon], point: np.array, max_dist: float

) -> List[Polygon]:

close_polygons = []

for poly in polygon_subset:

if np.linalg.norm(poly.center - point) < max_dist:

close_polygons.append(poly)

return close_polygons

# Rest of file (main, select_best_polygon).我们使用py-spy对其进行了分析,即使是我们最普通的简单翻译find_close_polygons方法为Rust代码也带来了超过10倍性能提升的改进。

我们对主要的占核心开销的代码片段进行了几次额外的迭代,直到我们最终在运行时获得了100倍的改进,同时保持了与原始库相同的API。

最终的Python代码如下:

import poly_match_rs

from poly_match_rs import find_close_polygons

class Polygon(poly_match_rs.Polygon):

_area: float = None

def area(self) -> float:

...

# Rest of file unchanged (main, select_best_polygon).Rust代码:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

use ndarray::Array1;

use ndarray_linalg::Scalar;

use numpy::{PyArray1, PyReadonlyArray1, ToPyArray};

#[pyclass(subclass)]

struct Polygon {

x: Array1<f64>,

y: Array1<f64>,

center: Array1<f64>,

}

#[pymethods]

impl Polygon {

#[new]

fn new(x: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>, y: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>) -> Polygon {

let x = x.as_array();

let y = y.as_array();

let center = Array1::from_vec(vec![x.mean().unwrap(), y.mean().unwrap()]);

Polygon {

x: x.to_owned(),

y: y.to_owned(),

center,

}

}

#[getter]

fn x(&self, py: Python<'_>) -> PyResult<Py<PyArray1<f64>>> {

Ok(self.x.to_pyarray(py).to_owned())

}

// Same for `y` and `center`.

}

#[pyfunction]

fn find_close_polygons(

py: Python<'_>,

polygons: Vec<Py<Polygon>>,

point: PyReadonlyArray1<f64>,

max_dist: f64,

) -> PyResult<Vec<Py<Polygon>>> {

let mut close_polygons = vec![];

let point = point.as_array();

for poly in polygons {

let norm = {

let center = &poly.as_ref(py).borrow().center;

((center[0] - point[0]).square() + (center[1] - point[1]).square()).sqrt()

};

if norm < max_dist {

close_polygons.push(poly)

}

}

Ok(close_polygons)

}

#[pymodule]

fn poly_match_rs(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_class::<Polygon>()?;

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(find_close_polygons, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}10、加餐

Rust(在pyo3的帮助下)以最小的代价为日常Python代码解锁了真正的原生性能。

Python对于研究人员来说是一个极好的API,而使用Rust制作快速构建块是一个非常强大的组合。

Proflier分析工具很不错,它能帮助你真正理解代码中发生的一切。

最后一点:计算机的运行速度实在是太快了。下次你在等待某件事完成时,考虑启动一个Proflier分析器,你可能会学到一些新东西。

原文链接:https://ohadravid.github.io/posts/2023-03-rusty-python/

译者介绍:

卢鑫旺,51CTO社区编辑,编程语言爱好者,对数据库,架构,云原生有浓厚兴趣。