在大语言模型中分离语言和思想

译者注:维特根斯坦提出他的“语言游戏”核心哲学概念的时候,还没有大语言模型,不然什么是语言活动的意义,如何通过语言的使用过程研究语义,怎样才能不把语言看作孤立静止的描述符号,而是看作体现生活的动态人类活动?什么又是大语言模型的建设性的、持续性的动态人类活动?遗憾人们已经没有机会听到这位哲学天才的看法了。

概要

大语言模型 (LLM) 是迄今为止所有模型中最接近掌握人类语言的模型,但对其语言和认知能力的看法仍然存在分歧。在这里,我们区分形式语言能力(语言规则和模式的知识)和功能语言能力(理解和使用世界上的语言)来评估 LLM。我们将这种区别建立在人类神经科学的基础上,该科学表明形式和功能能力依赖于不同的神经机制。尽管 LLM 在形式能力方面出奇地出色,但他们在功能能力任务上的表现仍然参差不齐,并且通常需要专门的微调和/或与外部模块耦合。我们假设以类似人类的方式使用语言的模型需要掌握这两种能力类型,这反过来又可能需要涌现出专门用于形式语言能力的机制,这与功能能力不同。

关键词:LLM,语言与思想,认知神经科学,语言能力,计算建模

语言与思想的融合

当我们听到一个句子时,我们通常会假设它是由一个理性的、有思考的智能体(另一个人)产生的。人们在日常对话中产生的句子通常基于他们的世界知识(“并非所有的鸟都能飞”)、推理能力(“你 15 岁了,你不能去酒吧”)和目标(“请你送我一程吗?”)。因此,我们经常使用其他人的陈述作为了解他们思想的窗口。

1950 年,图灵 (Alan Turing) 利用语言和思想之间的这种紧密关系提出了他著名的测试[1].图灵测试使用语言作为认知的接口,允许人类参与者探索两个对话伙伴的知识和推理能力,以确定他们中谁是人类,哪个是机器。尽管图灵测试的实用性此后一直受到质疑,但它无疑塑造了当今社会对机器智能的看法[2].

图灵测试的流行,再加上日常生活中的语言-思维耦合,导致了与语言-思维关系相关的几个常见谬误。一个谬误是,擅长语言的实体(无论是人类还是机器)也必须擅长思考。如果一个实体生成长而连贯的文本,它必须具有丰富的知识和推理能力。让我们称之为 “擅长语言 -> 擅长思考”的谬误。由于最近 LLM (LLM;见词汇表) 的兴起,这一谬误已经走到了最前沿。包括 OpenAI 的 GPT 模型、Anthropic 的 Claude 和更开放的替代方案[3]就像 Meta 的 LLaMa 模型和 EleutherAI 的 GPT-J 一样。今天的 LLM 可以生成与人类输出难以区分开来的文本,在某些文本理解任务中胜过人类[4,5],并在下一个单词预测上表现出超人的性能[6].因此,大众媒体和学术文献中都出现了这样的说法,即 LLM 不仅是语言处理领域的重大进步,而且还显示出“通用人工智能的火花”[7]. 然而,在评估 LLM 的能力时,重要的是要区分他们的思考能力和语言能力。“擅长语言 - >擅长思考”的谬误很容易将两者混淆,导致人们错误地将智力和意向性归因于最基本的对话系统(例如,1960 年代的聊天机器人 Eliza[8]).

这种谬误的反面是,一个不善于思考的模型也一定是一个糟糕的语言模型。让我们称之为 “糟糕的思考 -> 糟糕的语言” 谬误。LLM 通常因其缺乏一致、可推广的世界知识而受到批评[9],缺乏常识性推理能力[10],以及无法理解话语的真正含义[11].基于这些证据,一些批评者认为,这些模型未能产生完全捕捉人类思想丰富性和复杂性的语言输出,这意味着它们不是人类语言的良好模型。

“擅长语言 ->擅长思考 ”和“不擅长思考 -> 不擅长语言”的谬误都源于语言和思想的混为一谈。这种混淆并不奇怪:遇到一个尽管缺乏人类身份但能产生流畅句子的实体仍然是新奇的,因此也是不可思议的。因此,我们用于理解语言模型正在做什么的启发式方法(从我们与其他人的语言经验中出现的启发式方法)被打破了。

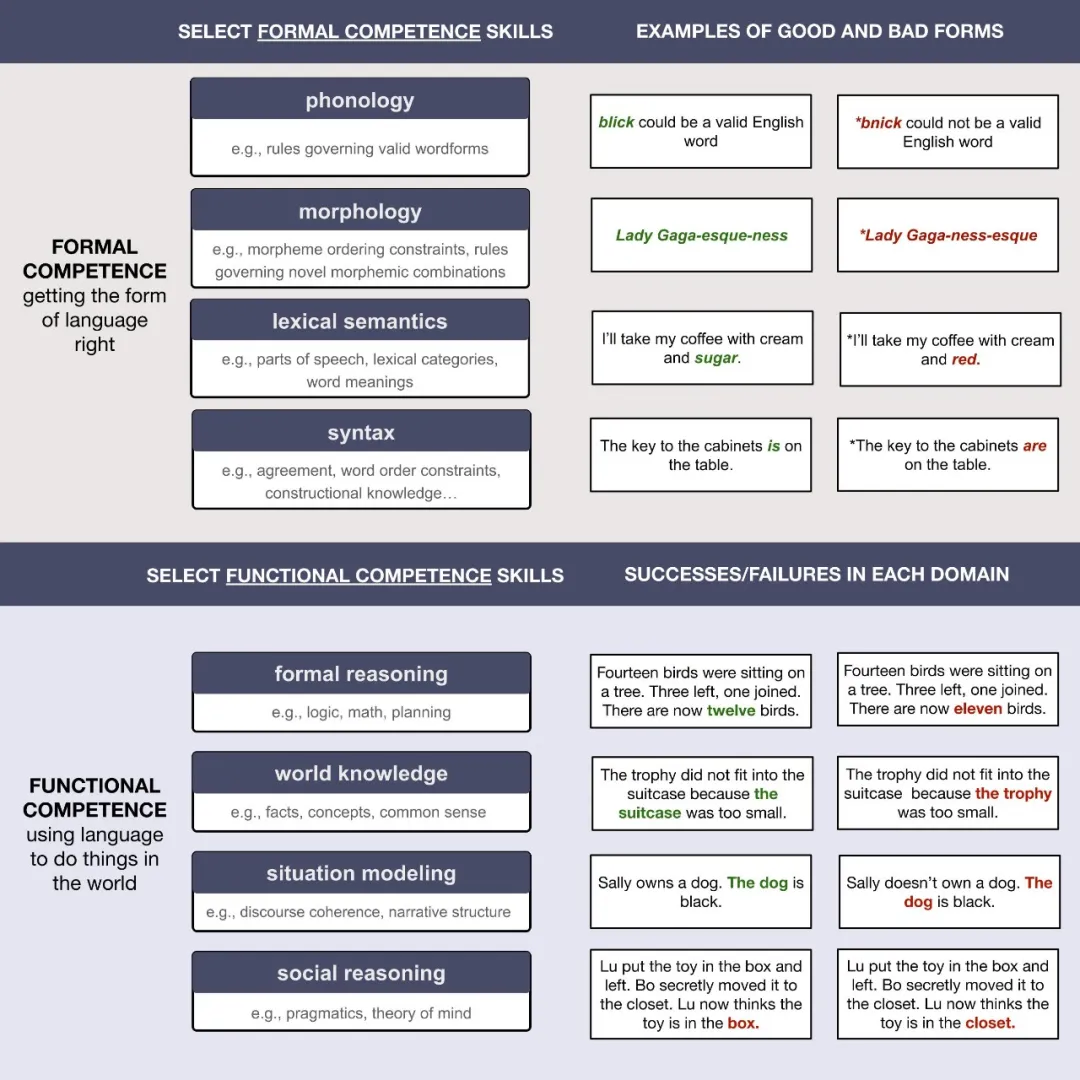

为了减轻语言与思想融合的谬误,我们建议系统地区分两种语言能力:形式语言能力——对语言规则和统计规律的了解——和功能语言能力——在现实世界中使用语言的能力。我们进行形式/功能区分的动机来自人脑,在这些大脑中,这些技能是强烈可分离的。形式和功能性语言能力都是人类语言使用的重要组成部分:一个有效的沟通者需要产生语法、有意义的话语,并战略性地使用这些话语来实现多样化的、依赖于上下文的目标[12,13].

有了这个区别,我们评估了当代LLM的能力,并认为LLM在形式能力和功能能力技能之间表现出差距:对于现代LLM来说,英语的形式能力接近人类水平,而他们的功能能力仍然不完整,结果取决于特定的功能能力领域和这些领域的任务。此外,虽然 LLM 中的形式语言能力随着训练数据量的增加而大幅提高,但随着规模的增加,功能语言能力的改进则不太一致,因此 LLM 开发人员现在已经从语言预测任务的简单扩展转向针对感兴趣行为的更专业的方法(例如,来自人类反馈的强化学习:RLHF [14]) 或将 LLM 与外部专用模块耦合(导致所谓的“增强语言模型”;[15]).

因此,我们判断下一个单词预测目标允许模型掌握形式但不一定是功能性的语言能力。掌握功能能力所需的内容更难确定,部分原因是人类的大部分认知(常识推理、科学知识、日常知识)可以通过语言传达,从而从语言中学习——即使这些能力本身并不是语言的。因此,语言模型获得了各种非语言能力。但是,正如我们所讨论的,功能能力的最终上限取决于关于语言信号中包含的信息以及用于使用该信息的机制的重要开放性问题。

在本文的其余部分,我们开发了一个框架,从认知科学的角度评估现代语言模型的能力。在第一部分中,我们详细阐述了形式和功能语言能力的结构,并根据人类神经科学的证据来激发这种区别。在第二部分中,我们讨论了 LLM 在实现形式语言能力方面的成功,表明在单词上下文预测上训练的模型捕获了许多复杂的语言现象。在第三部分中,我们考虑了功能语言能力所需的几个领域——形式推理、世界知识、情境建模和社会认知——今天的 LLM 在这些领域经常失败,或者至少表现比人类差。在第四部分中,我们讨论了我们的框架对构建和评估未来语言和思维模型的影响,然后在最后一部分总结了我们的主要结论。

形式语言能力与功能语言能力

语言能力意味着什么?

形式语言能力

我们将形式语言能力定义为产生和理解给定语言所需的一组能力。广义上讲,形式胜任意味着掌握正确的语言形式:知道哪些字符串可以是语言的有效单词(例如,bnick 不能是英语单词,但 blick 可以)[16]), 如何有效地组合语素以形成新词(例如,奧巴馬-less,而不是奧巴馬-ness-less)[17]),学习足够的单词含义,知道哪些单词可以进入句子中的哪些插槽[18],并知道如何将单词组合成有效的句子。

由于它在语言学史上的核心地位,我们在讨论形式能力时关注的是其中的最后一部分(将单词组成句子)。大多数标准书面英语的用户说,“The dogs in my bedroom are asleep”而不是“The dogs in my bedroom is asleep”,因为动词“to be”必须与作为句子主语的名词(“the dogs”)的形式相匹配,即使该动词更接近中间的单数名词(“bedroom”)。语言能力还需要对特殊语言结构的规律性具有极好的敏感性。例如,尽管说英语的人知道不要将不定冠词 “a” 与复数名词一起使用——这会使像 “a days” 这样的短语格式不正确——但他们也知道,在形容词和数字介入的特殊结构中,允许使用不定冠词 “a beautiful five days in New York”[19,20].

人类语言用户可能会学习规则,以及数千种特殊的结构[21],通过某种复杂的统计学习组合[22,23,24]以及先天的概念和/或语言机制[25,26,27].其结果是人类能够理解和产生语法和连贯的语言话语。

功能语言能力

除了能够胜任语言的规则和统计规律外,有能力的语言使用者还使用语言在世界上来完成目标[28,12,29]:谈论可以看到、感觉到或听到的事物,对不同的话题进行推理; 提出请求; 哄骗、搪塞和奉承。人们将语言与其他感知和认知系统(例如我们的感官和记忆)结合使用,并将词语作为我们复杂的社交技能支持的更广泛交流框架的一部分。孤立的形式语言系统除非能够与其他感知、认知和行动交互,否则它是无用的。

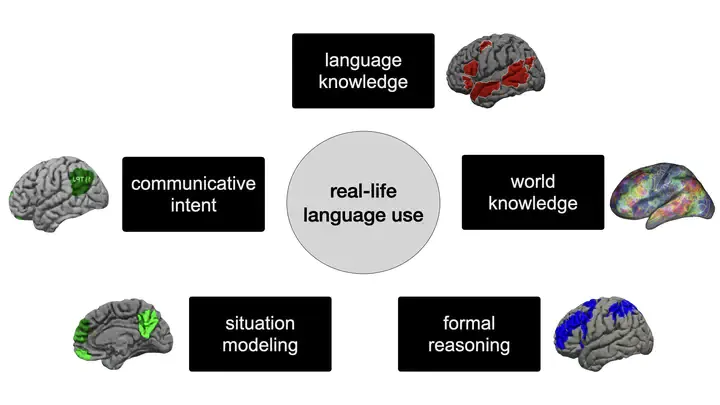

使用语言在世界上做事所需的能力与形式的能力不同,并且关键取决于非语言认知(图 1)。因此,我们将功能性语言能力定义为在现实世界环境中将语言与非语言特定能力结合使用时所需的非语言特定认知功能。

图 1:将形式能力和功能能力分开。语言的成功使用依赖于多种认知技能,其中一些(形式能力所要求)是特定于语言的,而另一些(功能能力所要求)则不是。确定特定失败是否源于形式能力或功能能力的差距是评估和改进语言模型的关键。

区分形式语言能力和功能语言能力的动机

我们区分形式语言能力和功能语言能力的动机来自我们对人类思维结构的了解。在人类中,语言与其他高级认知以及感知和行动紧密分离。下面我们简要总结了来自认知科学和神经科学的大量证据,这些证据支持这种分离。

语言网络支持人脑中的语言处理

人类语言处理利用额叶和颞叶(通常在左半球)中一组相互连接的大脑区域。此语言网络支持理解(口语、书面和手语)[30,31,32,33]和生成[34,35]; 对多个层次的语言规律敏感:从语音/子词汇[36]到短语/句子级别[37,38];并支持与词义处理以及组合语义和句法处理相关的语言操作[38,35].语言网络的破坏会导致语言缺陷[39,40].语言网络和语言功能之间的这种紧密联系表明,这些大脑区域负责人类的语言处理。

语言网络不支持非语言认知

语言网络对语言非常挑剔。语言处理和非语言能力之间强烈分离的证据来自两个主要来源:a) 神经正常成人的功能性脑成像研究,以及 b) 失语症患者的行为调查——失语症是一种通常由中风或退化引起的语言障碍。

功能性 MRI (fMRI) 等脑成像技术用于观察健康个体语言网络的实时活动。鉴于其高空间分辨率,fMRI 非常适合研究任何两种认知能力是否利用相同的大脑结构。例如,要询问语言和数学推理是否采用相同的大脑区域,我们可以让参与者在 MRI 扫描仪中执行语言任务和数学任务,然后测试在参与者解决数学问题时,在语言处理过程中活跃的大脑区域是否也活跃。这种方法揭示了语言网络对语言处理具有极强的选择性:当人们听、读或生成句子时,它会做出可靠的响应,但当他们执行算术任务、进行逻辑推理、理解计算机程序、听音乐、对物体或事件进行分类、推理人们的心理状态或处理非语言交际信息(如面部表情或手势)时,它不会做出响应[41,42,43,44,37,45,46,47,48].

对失语症患者的研究为测试哪些认知能力依赖于语言表征提供了一个独特的机会。特别令人关注的是“全面失语症”的病例,它会影响学习和理解。患有全面性失语症的个体表现出严重的语言缺陷,只留下一小部分单词。如果非语言认知的某些方面利用了与语言相同的资源,那么具有严重语言缺陷的个体应该总是在相关的非语言任务上表现出受损的表现。然而,尽管语言能力几乎完全丧失,但患有严重失语症的人可以拥有完整的非语言认知能力:他们可以下棋、解决算术问题、利用他们的世界知识来完成不同的任务、推理因果关系以及驾驭复杂的社交场合[49].

总之,来自脑成像研究和失语症患者的证据非常一致:在人脑中处理语言的机制不支持非语言认知任务。这种尖锐的分离表明,在检查语言模型的功能时,我们应该将它们的语言能力与它们的抽象知识和推理能力区分开来,这些能力可以通过语言界面进行探测——甚至可能学习——但需要的不仅仅是形式语言能力。

LLM在很大程度上掌握了英语的形式语言能力

在 2019 年的一次采访中,乔姆斯基评论道[50]:“我们在这里必须问一个问题:[深度学习] 是工程还是科学?[…]从工程的角度来看,它有点值得拥有,就像推土机一样。它能告诉你关于人类语言的任何信息吗?不能。深度学习模型不具有科学意义的观点在语言学中仍然很常见,尽管有许多争论将深度学习模型整合到人类语言处理和习得的研究中[51,52,53]以及他们应该作为语言和认知模型认真对待的论点[54,55,56],它们与语言研究的整合仍然遇到阻力。

在本节中,我们通过询问这些模型是否在实现形式语言能力方面取得了进展来评估 LLM qua 语言模型的性能——这种能力由人脑中的语言选择网络支持。我们认为,LLM 在掌握形式能力方面取得了惊人的成功——它们的形式语言能力与大约 2018 年之前的模型有质的不同,这是该领域很少有从业者预测的方式,而且这是出乎意料的,因为长期以来一直声称语法能力强的系统需要强大的特定语言先验。信息伴随惊喜:模型的成功为语言理论化提供了信息。

统计语言模型:一些基础知识

LLM 起源于计算语言学的几种早期方法,包括统计语言建模、词嵌入和联结主义(该方法的早期术语,后来演变成今天的深度学习)。与早期的统计语言模型类似,LLM 通常首先在单词预测任务上进行训练(与 20 世纪中叶 Shannon 的工作中用于训练 n-gram 模型的任务相同;请参阅[57]了解历史概述)。与分布语义和词嵌入中的方法类似(有关概述,请参阅[58,59]),LLM 将语言信息表征为高维空间中的向量。与早期的连接主义方法类似[60,61],LLM 是神经网络 — 一类机器学习系统,最初受到人脑的启发,并从输入数据中学习其参数。所有这些方法都与使用显式、结构化的语法规则分层表征的模型形成鲜明对比(见[62])来讨论这两种不同的范式)。

N-gram 和单词嵌入模型在自然语言处理的各个领域(例如,拼写更正、垃圾邮件分类、情感分析)都取得了一些成功。然而,他们从未在文本生成等一般语言任务上接近人类水平的性能,因此声称纯粹的统计方法永远无法捕捉自然语言的丰富性,尤其是在复杂的句法、形态和语义领域[例如,63]. 例如,有人声称,使用线性单词字符串作为输入的统计方法原则上无法学习需要分层表征短语和句子的罕见和复杂的句法特征[64].这种悲观主义现在受到了 LLM 的挑战。

LLM 通常首先在由来自 Web 的大量文本构建的训练集上进行训练。在预训练期间,LLM 有一个简单的目标:预测一个保留词元(LLM 中的基本单位 - 通常但并不总是对应于单词或语素[65]) 的词元。然后将预测的词元与真实值(该句子中实际出现的词元)进行比较,并将错误信号传播回模型以更新其许多参数。词元预测目标通常用作预训练步骤,然后针对更具体的任务对模型进行微调。

改变原规则并关注这些模型仍然无法做到的事情虽然很诱人[66],我们认为 LLM 捕捉各种语言现象的能力的显着进步不应被忽视。在 GPT-2 或 BERT 规模的模型中出现重要的形式语言能力,并且在代 LLM 中似乎处于很高水平。

LLM学习人类语言处理的核心方面

为了使 LLM 可用作人类语言处理的模型,我们必须确信这些模型编码了表征人类语言的抽象语音、形态、句法和语义规则。尽管 LLM 和人类的语言处理之间存在有趣的差异[70,71],也有一些重要的相似之处。在这里,我们回顾了 LLM 作为形式语言能力模型成功的证据。我们主要关注句法,展示了对语法基准的掌握证据以及 LLM 中涌现句法结构的证据。但是,在性能和涌现结构方面,类似的成功也已在其他语言领域(例如,涌现语音结构[72],富有成效地生成形态复杂的新词[73]、丰富的词汇语义信息[74]等)。

LLM 在不同语言现象的基准上表现良好

通过接受单词预测训练,transformer 模型可以学习很多关于语言结构的知识,包括即使在最近也被认为超出了统计模型范围的语言特征。这些模型不仅在 NLP 社区开发的一般语言理解测试中取得了成功(例如 GLUE 任务[75]),对我们来说,关键还在关于英语和其他语言的语言能力测试,这些语言有大量的语料库可用。

基准测试 BLiMP[76],例如,包含各种复杂语言现象中的最小语法与非语法句子对,诸如填充间隙依赖关系(“Bert know what many writers find”与“*Bert know that many writers find”)和负极性项目(“The truck has clearly tipped over”与“*The truck has ever tipped over”)。引人注目的是,一个模型[77]提交至 BabyLM 挑战赛[78]在 BLiMP 上达到 86%(参见人类基线 89%),尽管接受的训练数据量与人类儿童可能接触的数据量相当。模型在其他语言基准测试(如 SyntaxGym)上也取得了同样令人印象深刻的结果[79],现在有几十种对特定复杂语言现象的研究(其中一些我们将在下面讨论)。

LLM 学习层次结构

在人类语言中,单词被组合起来以产生组合意义。在一个多词的句子中,单个单词的含义并不是简单地一个接一个地线性添加。相反,它们可以按层次结构组合成树状结构。

语言中的层级结构以多种方式表现出来。一个突出的例子是非局部特征约定。在英语和许多其他语言中,动词与主语一致。例如,复数主语使用动词“are”,而单数主语使用“is”。二元语法模型(仅存储两个单词的字符串的频率)可以通过知道“keys are”比“keys is”更常见来了解“The keys are on the table”比“The keys is on the table”更有可能。但是这样的模型无法学习主语和动词一致,即使相距甚远:例如,“The keys to the old, wooden kitchen cabinet are on the table”在主语和动词之间有六个中间词,但“are”仍然与“keys”一致,而不是“cabinet”一致。然而,一个学习英语底层层次结构的模型应该能够跟踪这种长距离的主谓依赖关系[80].

今天的 LLM 执行远高于偶然性的长距离数字一致性,即使存在干扰词,他们也更喜欢语法而不是非语法的句子接续[81,82],尽管一些早期的模型可能会被频率效应(例如单数和复数形式之间的频率差异)分散注意力[83]). 同样,LLM 可以处理其他需要复杂层次结构的结构,例如 filler-gap 依赖项[84].最后,检查模型句子表征的内部几何结构的研究[85],对模型内部表征进行因果干预的研究[86],以及打开和关闭特定模型“神经元”的研究[87,88]为 LLM 如何表征层次结构和建立非局部结构依赖关系提供了机制见解。

LLM 学习语言抽象

后续[89],我们将抽象定义为一种广义的语言表征——例如词性类别(例如,名词或动词)或语法角色(例如,主语或宾语)——它超越了简单的输入存储并支持泛化。上一节中概述的主谓一致概念本身依赖于主语和动词的抽象类别。如[81],在像“dogs in the neighborhood often...(bark/barks)“,模型可能会学习约定规则的浅层版本,即”dogs“和”bark“在同一句子中的搭配比”dogs“和”barks“更常见。但是,具有语法主语、语法数字和动词等类别的抽象表征的模型应该能够处理长距离数字一致性,即使对于新颖的单词组合也是如此。

测试模型对抽象规则的了解的一种方法是使用语义上无意义的句子,例如“我和椅子一起吃的无颜色的绿想法......(sleep/sleeps)”。模型已被证明在多种语言中都能很好地执行一致性任务,即使是在这些语义异常的句子上也是如此[81].

一个更严格的语言抽象测试是 LLM 是否可以将形态句法规则应用于新词。BERT 抽象能力研究[90]表明 BERT 具有一定的概括语法类别的能力。它们为模型提供短语中使用的新词作为输入(例如,“the blick”,其中 blick 可能是名词,“they dax”,其中 dax 可能是动词),并测试模型是否可以根据输入概括词性类别(例如,为“I went to a blick”分配比“I went to a dax”更高的分数)。他们得出结论,BERT 在这项任务上取得了部分成功:它确实学会了泛化,但只有在重复示例之后[但请参阅91,92,了解单词本身影响编撰能力的方式].模特似乎也(经常)能够适当地使用新词[69,73].

大量工作使用一种称为探测的方法测试了 LLM 中的语言抽象[93,94].在本文献中,分类器通常被训练为将内部模型表征作为输入,然后预测抽象类别作为输出,例如词性或依赖关系角色。探针的逻辑是测试这些抽象类别是否可以成功地从内部模型状态中恢复。使用这种方法,有人声称 LLM “重新发现了经典的 NLP 管道”[95],在各个层学习词性类别、解析、命名实体和语义角色等特征(尽管参见[96]).

重要的是,类人语言模型不应仅依赖于抽象规则。人类在语言学习和处理中使用不同的线索,这些线索有时会覆盖严格的分层句法处理或与之冲突[例如,97,98]. 人类在不同程度上也依赖于记住以前看到的输入,而不是纯粹应用抽象规则[89,21]. 因此,在评估 LLM 的形式能力时,必须直接将它们的性能与人类的性能进行比较[99].例如,重新审查[100]早期研究[101]表明 GPT-2 中明显的句法一致性缺陷发生在对人类也具有挑战性的实例上。总的来说,LLM 显然学习了一些语言抽象,即使这种抽象的程度仍然是一个有争议的问题(就像对人类一样)。

LLM 学习结构

最近的证据表明,LLM 学习句法结构[102,103,104].这些结构可以是特殊的、词汇敏感的,并且相对罕见,例如“a beautiful five days in Austin”[105]. LLM 还对介词短语中的前置结构表现出一定程度的敏感性(“Surprising though it may be...”),即使间隙跨越了有限子句边界(“Surprising though I know it may be”)[106]. 他们实现了这种敏感性,尽管这种跨越有限子句边界的例子非常罕见:语料库中的 70 亿个句子中只有 58 个例子。模型可以学习到一些非常罕见的结构是语法的,而其他同样罕见的结构不是,这一事实表明 LLM 有意义地学习了一些关于语法的知识。

模型对比较相关词 “The better the syntax, the better the semantic” 的形式也很敏感[107]. 然而,这种敏感性并不意味着他们对结构的语义含义敏感。事实上,基于这些句子的推理似乎是一个挑战(例如,知道如果我说“语法越好,语义越好”,然后告诉你语法更好,这意味着语义更好)。这种不对称很好地说明了形式/功能的区别:模型显然知道如何使用结构并获得正确的形式,而不一定能够获得预期的含义。我们将在后面的部分中更详细地讨论这些问题。

LLM 可以预测人类语言网络中的活动

如上所述,人类的语言处理依赖于专用的大脑网络。这个网络展示了形式语言能力的所有特征:它对孤立短语和句子中的抽象层次结构规则很敏感[31,108,109,110],体现在自然风格的叙事[111,112,113,114],以及句法格式良好但空语义 (“jabberwocky”) 促进因素中[31,49,109]。语言网络对特定的单词共现也很敏感[例如,对 n-gram 意外的敏感性证明;111],表明它不仅学习规则,还学习语言模式。语言网络对语言输入与非语言输入的选择性,以及它对语言规则和模式的敏感性,使我们能够将形式语言能力作为一组在人类中发生在语言网络内的计算来操作。

如果 LLM 和人类语言网络执行类似的计算来实现形式语言能力,我们期望在它们的内部组织中观察到相似性(参见[55]在视觉领域中也有类似的论点)。事实上,LLM 和人类语言网络表现出非同寻常的相似之处。

首先,LLM 的内部架构类似于语言网络的内部架构。两者都在抽象语言单元(单词/词元)的级别上运行,而不是在特定模态的表征(如像素或声学波形)的级别上运行,并将这些单元级别的表征组合成短语和句子的复合表征。这两个系统都没有显示句法和语义处理的明确空间分离 (LLM:[95,115];脑:[38,114]),表明这些过程在两者中都是紧密耦合的。

其次,可以在语言网络的内部 LLM 表征和神经活动模式之间建立直接映射。这种映射可以成功地用于预测大脑在以前看不见的上下文中对新句子和单词的反应[116,117,118].LLM 和大脑中的句子激活模式之间的这种相似性表明了支持这些系统中计算的相似表征机制。

我们并不声称 LLM 和语言网络之间的对应关系是一一对应的。例如,LLM 学习传统人类语言能力之外的模式,例如预测换行符[119].尽管如此,当代 LLM 学习的内部表征包含足够的信息来预测语言网络对不同语言字符串的响应这一事实表明 LLM 的表征与语言网络中的表征之间至少有一些对应关系。

使用 LLM 作为人类形式语言能力的模型

今天的 LLM 生成高度连贯的语法文本,这些文本可能与人类输出无法区分。在此过程中,他们展示了层次结构和语言抽象的知识,同时类似于语言处理过程中的人脑反应。这些模型不是抽象语言规则的完美学习者,但人类也不是。因此,我们得出结论,LLM 具有相当多的形式语言能力,至少在英语方面是这样。

LLM 已经推翻了关于仅从语言输入的统计数据中获得某些语言知识(包括层次结构和抽象类别)根本不可能的说法[120].如果语言建模继续改进(包括从更真实的类型和大量的数据中学习),这将允许测试这个 “刺激贫乏 ”论点的更一般版本[121],包括对成功学习人类语言的规则和统计规律可能需要哪些归纳偏差的具体测试。因此,LLM 在语言学习和处理的科学研究中具有重要价值。

非增强 LLM 在功能语言能力方面存在不足

如果没有非语言的认知技能,就不可能在现实生活中使用语言。理解一个句子,推理它的含义,以及决定如何回应,都依赖于超越形式能力的认知能力。在本节中,我们要问:当代LLM在功能语言能力方面的表现如何?

我们专注于四种关键能力,这些能力不是特定于语言的,但对于现实生活中的语言使用至关重要:i) 形式推理——一系列能力,包括逻辑和数学推理、计算思维和新问题解决; ii) 世界知识——关于智能体、对象、属性、行动、事件和想法的事实和常识性知识; iii) 情境建模 — 随着叙述/对话的展开,对对象、代理和事件进行动态跟踪; iv) 社会推理——理解语言交流的社会背景。普通的对话需要使用所有这些能力,但没有一个是特定于语言使用的能力。

对于每个领域,我们首先描述它在人类中的神经机制,然后讨论当代 LLM 对该领域的掌握程度。我们得出的结论是,与形式能力不同,LLM 的功能能力是不平衡的,通常需要专门的微调和/或缺乏类似人类的稳健性和通用性。我们强调正确评估 LLM 的重要性;评估问题可能发生在形式或功能能力的研究中,但我们认为它们导致了对模型功能能力的大量鼓吹。

形式推理

语言允许人们讨论高度抽象的想法,将想法转化为科学和哲学理论,构建逻辑三段论,并参与形式辩论。不出所料,语言通常被认为是复杂推理的基石[136,137]. 然而,神经科学提供的证据表明,语言和形式推理在认知系统中是分离的,因此掌握了形式语言能力的模型不一定会表现出逻辑推理能力。

人类:尽管语言和推理相互作用密切,但它们依赖于不同的认知和神经系统。与语言不同,形式推理涉及称为多重需求网络的大脑区域 [138],之所以这样命名,是因为这些区域从事许多认知要求高的任务:逻辑[47]、数学推理[41]、物理推理[139]和计算机代码理解[140,46].对人类患者的研究为多需求网络在逻辑推理中的作用提供了因果证据,表明这些区域的损伤量与智力流标准测试的表现呈负相关[141,142].重要的是,即使任务是以语言方式呈现的,多重需求网络也支持推理[41,140,47]— 类似于 LLM 接收提示的方式。

LLM:多项研究指出 LLM 在需要形式推理的任务(例如数学问题)方面的局限性。GPT-3 在两位数加法和减法方面表现良好,但在更复杂的任务上表现不佳,例如三位数加法或两位数乘法[69].GPT-4 同样在小数字数学运算上表现出良好的性能,但在高位数数学运算上则不表现出良好的性能[143].破坏输入中常见共现模式或需要多步骤操作的推理测试也会导致模型失败[144,145].

这些失败最常被引用的原因是人工神经网络无法推广到其训练分布之外的模式[145,146].这种泛化差距可以通过 “思维链 ”方法部分弥合,即提示模型在得出答案之前生成中间计算步骤[147].然而,即使这些方法也不会带来万无一失的结果[143].因此,越来越多的研究人员将 LLM 与可以执行结构逻辑和数学计算的外部模块配对,例如 Mathematica 插件[148]或概率推理引擎[149].转向用推理特定模块来增强 LLM与神经科学的证据一致:语言和形式推理是不同的认知能力,当它们得到单独的处理机制支持时效果最佳【译者注:推理部分的scaling law会构建或完善目前缺失或羸弱的变分推理机制。

世界模型 1:事实和常识

LLM 中一个经常争论的能力是它们利用内部世界模型的能力[150,149].我们将世界模型的概念分为两个部分:世界知识(事实和常识,本节)和态势追踪(维护和更新有关对象、代理等的信息的能力;下一节)。

人类:来自神经科学的证据表明,语言和语义(世界)知识之间存在分离。有语言缺陷的人可能难以产生语法话语和检索上下文合适的单词,但他们对非语言呈现的物体和事件的推理能力通常保持不变[151,42].另一方面,患有语义性痴呆(一种神经退行性疾病)的人保留了说话的能力,但在以非语言方式呈现为图片的刺激下,很难完成依赖世界知识的任务(例如,知道南瓜通常是橙色的)[152].因此,语言和语义知识可以解耦。

LLM :LLM 可以访问有关世界的丰富知识:Web 文本中的单词共现模式包含事实信息(例如,谁是第一个登上月球的人)和常识信息(例如,柠檬的味道)[153]. 如果可以有效地提取这些信息,LLM 将能够作为现成的知识库[154].然而,LLM 表征中包含的世界知识存在几个主要缺点。

首先,LLM 经常产生虚假陈述,非形式地称为“幻觉”。这一观察并不令人惊讶:他们的训练目标是生成合理的句子延续,而不参考结果声明的基本事实正确性。一些开发人员已经微调了 LLM,以提供指向支持其主张的来源的链接;但是,这些引用也可能不准确[155].

其次,LLM 输出通常不一致:以不同方式表达相同的提示可能会引起不同的响应[156].他们也可能通过干预信息来“分散”注意力,例如,在前提和结论之间插入不相关的声明[92].

第三,常识性知识在语言语料库中往往代表性不足:人们更有可能传达新的或不寻常的信息,而不是众所周知的事实[157].因此,LLM 可能会在常识性知识基准上苦苦挣扎[158],尤其是在控制了低级统计提示之后[9].

第四,明确陈述的事实知识很容易获得,但很难维护,需要不断更新;例如,“Who is the current president of US?”的答案每 4 年或 8 年就会改变一次。虽然人类可以通过一个句子来更新他们的知识表征,但在 LLM 中更新世界知识需要在其内部参数中定位和编辑这个特定的知识——这是一项非同小可的任务[159],特别是因为这些编辑应该会影响其他一些知识(例如,以前的现任总统现在是以前的总统),但许多其他事实不受影响[160].

更像人类的世界知识表征方法可能需要将语言表征/处理和世界知识存储/更新分开。存在这样的方法[例如,161]但尚未在该领域占据主导地位,通常是因为现有知识库的覆盖率相对较低。虽然我们不能仅仅依靠 LLM 来准确地宣称世界知识,但我们可以将它们用作构建详细知识库的起点[162]和 常识大纲[163].

世界模型 2:态势追踪

人们可以跟随跨越多个章节甚至多本书的故事情节。我们还可以在交谈数周或数月后记住许多细节。我们通过利用语言输入来创建“情境模型”来完成这些壮举——一个包含实体、它们之间的关系以及它们所处状态或参与的事件序列的心智模型[164]. 人类的语言网络是否根据其输入构建了一个情境模型?随着时间的推移,LLM 在构建和更新情境模型方面有多好?

人类:人类的语言网络似乎没有跟踪子句级别以上的结构[165,166]. 相反,在较长时间内的意义整合很可能发生在所谓的默认网络中[167]. 至关重要的是,默认网络同时跟踪语言和非语言叙述[168],表明情境建模不是特定于语言的技能。

LLM :LLM 中的情境建模面临两个主要挑战:(1) 从连续的许多句子中提取信息;(2) 集成传入的输入以适当更新有关实体及其状态的信息。

第一个问题是目前通过不断增加模型的上下文窗口来解决的,即它们可以一次性处理的单词数量。这种方法将不可避免地遇到计算挑战:在总结一本书时,拥有一个同时关注该书中每个单词的模型效率非常低(尽管请参阅一些克服此问题的尝试,例如,[169]).此问题的类似人类的解决方案可能包括分层处理,例如,为每一章生成摘要,然后为整本书生成摘要(有关相关方法,请参阅170,171).

即使 LLM 在较短的文本跨度上运行,可以轻松适应其上下文窗口,问题是:它们能否更新其内部表征以跟踪世界的变化?一些证据表明他们可以[172],尽管 LLM 在情境建模时会犯典型的非人类错误:例如,它们的输出可以引用不存在的话语实体(“Arthur 不拥有一只狗。这只狗是棕色的“。[173]).因此,使用仅 LLM 架构在较短的文本跨度上构建稳健的情境模型是否可行仍然是一个争论的问题。

社会推理

“水!”

维特根斯坦 (Wittgenstein) 使用像这样的单个词话语来表明语言意义从根本上取决于上下文。虽然这个词的字面意思很简单,但预期的含义却更加多样化。这个词是被沙漠中口渴的人喘着气说的吗?徒步旅行者警告他的朋友有一条看不见的溪流?一个不耐烦的食客与服务员交谈?认知科学和语言学的研究已经认识到,语言的这些与上下文相关的方面不是次要的,而且是人类语言生成和理解的核心部分[28,12].

在字面内容之外推断话语的预期含义所需的一组技能称为语用学。语用学可能涉及各种神经机制[174,175,176],包括语言网络和其他大脑区域。因此,不同类型的语用推理可以归类为形式能力或功能能力。在这里,我们专注于语用学所需的一个核心功能能力:社会推理。

人类:大量的神经科学证据表明,人脑有专门的机制来处理社会信息[44,177].与我们当前讨论最相关的是心智网络理论[178],当它们的主人试图推断其精神状态时,一组大脑区域参与其中(我们不使用语言;[179,180]). 心智网络理论对语言理解的具体贡献可以分为两大类。首先,就像其他功能专门的大脑模块一样,它在处理与其领域特别相关的语义内容时参与其中:需要推断角色心理状态的叙述涉及心智网络理论[180],而需要推断人物意图的文本比那些不需要的文本更能引起兴趣[181,182]. 其次,在非文字语言理解过程中,心智网络理论的参与度更高,包括笑话、讽刺、间接引语和对话暗示等现象[183,176] --换句话说,在理解话语的含义需要推断说话者的意图的情况下。因此,成功的语言理解依赖于我们更广泛的、非特定语言的社交推理技能。

LLM:使用 RLHF 训练的最新模型在解释非字面话语(例如隐喻和 礼貌的欺骗,表明他们至少可以在一些实用任务上达到人类或接近人类的表现[184]. 也就是说,LLM 在语用领域表现出不平衡的表现:即使他们的隐喻理解能力飙升,他们解释讽刺或完成笑话的能力也是有限的[184].总的来说,至少某些形式的语用推理可以通过有针对性的微调获得。对于LLM来说,最容易使用的语用学方面是否是人类语言网络所支持的方面,仍然是一个悬而未决的问题。

LLM 解决心智理论任务的能力一直受到特别的争议。这些任务既需要社交知识,也需要维护情境模型的能力。一个典型的示例是角色 X 将对象从位置 A 移动到位置 B,而角色 Y 不在身边,因此看不到移动。目标是预测对象的真实位置(位置 B)和角色 Y 认为对象所在的位置(位置 A)。经过教学调整的 LLM 已经掌握了心智理论任务[185]的大胆宣称,很快就被一个演示所反驳,该演示包括基本控制(例如告诉角色 Y 的真实对象位置)将 LLM 性能降低到低于概率的水平[186]. 其他几项研究确定了 LLM 在心智理论任务方面的表现存在局限性[187,188,189,参见。190].克服这些限制的一种解决方案是通过实体状态和角色信念的符号跟踪器来增强 LLM[191],这种方法反映了人类语言和心理处理理论之间的分离。

语言输入可以引导功能能力

许多非语言认知能力可以通过语言输入得到显著增强。在人类中,这种关系在发育过程中尤为突出:当婴儿有语言标签陪伴时,他们更容易学习新的概念类别[192],而语言使用延迟的儿童也会延迟社交推理能力[193]. 即使在成年后,对特定数字的了解也能预测在概念上表征精确数字的能力[194]. 再加上语言输入包含有关世界的大量信息,并且语言既是人们大部分世界知识的关键数据源又是表征基础,这一证据表明,原则上,仅根据语言输入训练的模型可以获得大部分功能性语言能力。

因此,我们并不认为功能语言能力对于基于语言的模型来说是遥不可及的; 我们的主要目标是 (1) 强调形式语言能力和功能语言能力之间的概念区别——在人脑中利用不同的神经回路,以及 (2) 展示 LLM 的形式语言能力和功能语言能力之间的鸿沟。这些事实导致了一种推测,即与人脑一样,能够掌握语言使用的模型也需要或受益于形式和功能能力的单独机制。接下来我们讨论这个想法。

迈向像人类一样使用语言的模型

在本文中,我们提出了一个论点,即形式语言能力和功能语言能力是不同的能力,形式能力依赖于不同的语言机制和功能能力需要整合不同的大脑网络。我们已经表明,作为词语上下文中预测目标的结果,形式能力在当代 LLM 中出现;然而,仅靠这个目标似乎不足以使 LLM 具备功能性语言能力技能。根据神经科学证据,我们建议在现实生活中取得成功的语言模型需要模块化,模仿人脑中形式能力和功能能力之间的分工。

我们看到至少有两种方法可以分离负责形式和功能能力的 LLM 电路:将模块化显式地构建到系统的架构中(我们称之为架构模块化),或者通过训练过程自然地引入模块化,通过训练数据和目标函数(我们称之为涌现模块化)。

架构模块化有着悠久的历史;它涉及将单独的组件拼接在一起,可能使用非常专业的架构[195,196].现代示例包括与单独的内存模块配对的 transformer 语言模型[例如,161,197]或用于视觉问答的模型,包括语言模块、视觉模块和推理模块[198,199].这种模块化模型实现了高任务性能,效率更高(即,可以在较小的数据集上进行训练,并且在推理过程中具有较低的计算需求),并显示出更好的泛化性(即,在具有以前看不见的属性的数据集上表现良好)。这种模型的模块可以单独或一起训练,类似于人类在学习执行新颖的复杂任务时如何灵活地组合不同的认知技能。

最近,对这种模块化的需求已经扩展到包括尝试通过调用单独程序的能力来增强语言模型,例如包括 API 调用[200]、数学计算器[201]规划[202]以及执行特定结构化操作的其他类型的模块。

另一种方法使用 LLM 作为模块,将自然语言查询转换为代码,然后可以将其传递给符号模块,然后生成答案。[149]概述了这种方法的研究计划,表明经过微调以生成自然语言和代码 (Codex) 的 GPT-3 版本可以将文本输入转换为有意义的结构化概率程序; 这些程序中的推理可用于推理关系域(如亲属关系系统)、接地域(如视觉场景)以及需要计划和理解他人计划的情况。他们的方法展示了一条很有前途的途径,可以将 LLM 的成功之处(即形式语言能力)与其他受益于符号结构和抽象的认知模块相结合。

涌现模块化方法涉及端到端训练模型(类似于当代 LLM),同时创造条件,促进在训练过程中出现专门的模型子组件。模块化结构已被证明在语言以外的领域的一些端到端神经网络系统中自发出现[例如,203,204],这表明涌现模块化可能构成许多复杂任务的最佳解决方案。这种方法成功的一种策略是让模型架构激励模型内单个专用模块的开发。Transformer 是当今最流行的架构,它允许不同的注意力头关注不同的输入特征,从而在一定程度上满足了这一条件[例如205,206,207];某些方法更明确地促进了模块化,例如,通过赋予 transformer 一种专家融合架构,激励不同的 “专家” 执行不同的计算[208,209,210].

模块化模型架构与大脑的语言功能架构更加一致,后者包括用于形式和功能能力的单独组件。是否有可能构建不模仿人脑模块化结构的形式和功能能力的系统?理论上,是的:原则上,具有不同底层架构(例如,模块化与非模块化)的系统可以表现出相似的行为。然而,在架构级别明确解开形式和功能能力技能可能是确保 AI 模型以类似人类的方式使用语言的最万全的途径。

结束语

在过去的几年里,围绕语言模型的讨论包括一种怪异的高估和低估的混杂[66].一些人宣称模型正处于智能的边缘时,其他人则指出 LLM 在广泛的任务上的许多失败案例,从数字乘法到生成事实真实的陈述。在这里,我们将这些看似不一致的反应与计算语言学、认知科学和神经科学中先前和正在进行的工作进行了探讨。特别地,我们认为 LLM 在需要特定类型的结构和统计语言能力——形式语言能力的任务上非常成功。尽管它们的性能还不完全像人类,但这些模型在表征和使用单词之间的分层关系以及构建足够抽象以推广到新单词和结构的表征方面取得了令人印象深刻的成功。基于此,这些 LLM 在语言学中作为人类语言处理的候选模型还未得到充分利用。

我们还回顾了 LLM 在针对现实生活语言使用的任务(例如推理)上的一些失败,同时强调这些任务所需的能力与形式语言能力有着根本的不同,并且依赖于人脑中不同于语言处理机制的体系。

LLM 在非语言任务上的失败并不会削弱它们作为语言处理模型的效用。毕竟,支持人类语言处理的大脑区域也无法进行数学运算、解决逻辑问题,甚至无法跨句子或段落跟踪故事的含义。如果我们以人类的思想和大脑(广义智能的一个很好的例子)为指导,我们可能会预期,开发智能系统的未来进展将需要将语言模型与代表抽象知识并支持复杂推理的模型相结合【译者注:这跟译者的理解不谋而合,参见OpenAI o1 如何学会三思而后行】,而不是期望单个模型(使用单个单词预测目标进行训练)来完成所有工作。最后,为了检测和监测这些进步,我们还需要将形式语言能力和功能语言能力明确区分开来的基准。形式和严格地评估 LLM 中的功能能力将对科学和工程提供信息(见未决问题)。

对于那些认为人类语言最有趣的方面不能仅从数据中学习的人,我们说 LLM 令人信服地展示了从语言输入中学习复杂句法特征的可能性(即使截至目前,需要的输入比典型孩子接触到的要多得多)。对于那些批评 LLM 无法进行复杂算术或推理世界的人,我们说,让语言模型休息一下:鉴于人类思维中语言和非语言能力的严格区分,我们应该分别评估这些能力,承认形式语言能力的成功,即使非语言能力落后。最后,对于那些希望改进机器学习系统状态的人,我们建议,不断扩展(scaling up)模型的同时[213],更有前途的解决方案将以模块化架构(内置或涌现)的形式出现,这些架构与人脑一样,将语言处理与执行感知、推理和行动的其他系统整合在一起。

词汇表

•就我们的目的而言,抽象是一种允许泛化的语言表征。词性就是这样一个例子:“dog” 和 “cat” 这样的词属于 “名词” 的抽象类别。

•架构模块化涉及将不同的模块显式构建到计算模型中,每个模块负责实现不同的目标。

•微调是一个过程,通过该过程,在模型经过预训练后,它会接受针对新数据的额外训练,通常用于特定目的。

•形式语言能力是获得正确语言形式的能力。它包括构词知识(例如,音系学和形态学)、词义知识以及单词如何组合造句的规则和统计模式知识。请注意,我们对术语“能力”的使用与语言学中经典的能力/表现区别不同,因为在模型和人类中,区分能力和表现通常很困难。

•涌现模块化是指通过模型训练过程自然引入模块化,而无需将其显式构建到架构中。

•功能性语言能力是使用语言完成世界上事物的能力。它依赖于许多非特定语言的认知领域,如形式推理、世界知识、态势追踪和社会认知。

•层次结构是语言的一个重要属性,它使它不仅仅是一个线性的单词序列。相反,单词在句子中的组合方式最好通过树状结构来捕捉,其中一些单词和短语嵌套在较大的短语中。

•语言网络是一组相互关联的大脑区域,它们选择性地响应语言,但不响应非语言输入和任务。

•LLM (LLM) 是基于深度神经架构(通常但并不总是transformer)的模型,并使用上下文单词预测任务(有时在主要训练过程中或之后加入额外的训练目标)对大量文本进行训练。术语“大型”是指这些模型中的参数数量(从数百万到数十亿不等),以及训练数据的大小。

•预训练是这样一个过程:首先在常规任务(对于 LLM 中,通常是文本预测任务)上训练模型,然后再进行训练或用于更专业的目的。

•人类反馈的强化学习 (RLHF) 是一个过程,通过该过程,强化学习技术用于将人类偏好(例如,两个模型输出中的哪一个是首选的)传递给模型。它似乎导致了功能任务的显着改进。

•心智理论是一种认知技能,它使人们能够思考和推理他人的思想(即他人知道、相信、想要等)。

•词元是语言模型中的基本单位。在早期的语言模型中,它们通常是单词或语素。在当今的 LLM 中,它们通常是使用”字节对编码(Byte Pair Encoding)”等算法从大量文本中推断出来的。它们可以类似于单词和语素,但有时也可以用于子词或语言上非自然的单位。

要点

•形式语言能力(正确地掌握语言的形式)和功能语言能力(使用语言来实现世界上的目标)是不同的认知技能。

•人脑包含一个区域网络,这些区域选择性地支持语言处理(形式语言能力),但不包含其他领域,如逻辑或社会推理(功能语言能力)。

•在 2010 年代后期,在单词预测任务上训练的 LLM开始在形式语言能力方面取得前所未有的成功,在可能需要层次结构和抽象的语言任务上表现出令人印象深刻的表现。

•对于 LLM来说,在需要功能语言能力的任务上保持一致的性能更难实现,并且通常涉及下一个单词预测之外的增强。

•来自认知科学和神经科学的证据可以阐明 LLM的功能和局限性,并为更好的、类似人类的语言和思维模型铺平道路。

悬而未决的问题

•从语言信号中可以获得多少功能能力?人类使用语言作为知识的载体,因此 LLM 从语言信号中获取非语言信息。这个信号中有多少信息可以用来引导功能能力?功能性能力的某些方面是根本无法从语言中学到的吗?

•我们如何在少量数据上训练出称职的语言模型?LLM 已经取得了非凡的语言能力,但他们接受的数据训练与人类儿童所遇到的数据截然不同。尽管 LLM 接收的单词要多得多(几个数量级),但它们缺乏被认为对儿童语言习得至关重要的丰富结构和交互式输入。训练模型是否会以更具交互性和更像人类的方式产生好处?

•LLM 的形式能力成功会转移到其他世界语言吗?大多数 LLM 评估以英语和少数其他世界语言进行。为资源匮乏的语言构建模型并在形式和功能维度上评估它们是一个重要的持续项目。

•LLM 的增长将持续多久?10 年前,该领域的大多数研究人员都不会预料到 LLM 会像今天一样先进。当前的 AI 方法是否会在语言和思想方面带来进一步的革命性成就,或者掌握功能性语言能力是否需要全新的方法?

•哪个更有前途:架构模块化还是涌现模块化?如果我们想构建类似人类的模块化系统,是否需要明确构建功能不同的组件,或者可以通过端到端的微调来诱导它们,例如使用来自人类反馈的强化学习 (RLHF)?

•当今 LLM 的模块化程度如何?我们认为,同时获得形式能力和功能能力的 LLM 可能需要依赖针对不同能力类型的单独机制。机制可解释性研究可以揭示即使在今天的 LLM 中,不同的认知任务也可能在多大程度上分离。

•LLM 应该被描述为单个语言用户还是潜在用户输出的分布?在语言使用的上下文中,有多种方式可以考虑 LLM:例如,作为单个语言用户(“基于智能体的视图”)或作为增强人类活动的工具,如计算器(“基于工具的视图”)[214,215,216].随着 LLM 获得额外的能力并得到更广泛的使用,这些观点中的哪一种将是思考 LLM 的最富有成效的方式?

•LLM 需要多少基础才能继续改进?与跨不同模式的方法相比,纯文本方法的限制程度[217,218]?

•LLM 最终能告诉我们多少关于人类语言和认知的信息?LLM 作为人类语言使用模型存在哪些不足?这些差异是可以解决的,还是需要语言研究人员开发不同的范式?

参考文献

·[1] A. M. Turing.Computing Machinery and Intelligence.Mind, 59(October):433–60, 1950.Publisher: Oxford University Press.

·[2] Y. Chang, X. Wang, J. Wang, Y. Wu, L. Yang, K. Zhu, H. Chen, X. Yi, C. Wang, Y. Wang, et al.A survey on evaluation of large language models.ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 2023.

·[3] R. Bommasani, K. Klyman, S. Longpre, S. Kapoor, N. Maslej, B. Xiong, D. Zhang, and P. Liang.The foundation model transparency index.arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.12941, 2023.

·[4] A. Wang, Y. Pruksachatkun, N. Nangia, A. Singh, J. Michael, F. Hill, O. Levy, and S. R. Bowman.SuperGLUE: A stickier benchmark for general-purpose language understanding systems.In 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019.

·[5] A. Srivastava, A. Rastogi, A. Rao, A. A. M. Shoeb,etc. Beyond the imitation game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models.Transactions on Machine Learning Research, 2023.

·[6] B.-D. Oh and W. Schuler.Why does surprisal from larger transformer-based language models provide a poorer fit to human reading times?Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 11:336–350, 2023.

·[7] S. Bubeck, V. Chandrasekaran, R. Eldan, J. Gehrke, E. Horvitz, E. Kamar, P. Lee, Y. T. Lee, Y. Li, S. Lundberg, et al.Sparks of artificial general intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4.arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.12712, 2023.

·[8] J. Weizenbaum.Eliza—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.Communications of the ACM, 9(1):36–45, 1966.

·[9] Y. Elazar, N. Kassner, S. Ravfogel, A. Ravichander, E. Hovy, H. Schütze, and Y. Goldberg.Measuring and improving consistency in pretrained language models.Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 9:1012–1031, 2021.

·[10] G. Marcus.The next decade in AI: Four steps towards robust artificial intelligence.arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.06177, 2020.

·[11] E. M. Bender and A. Koller.Climbing towards NLU: On meaning, form, and understanding in the age of data.In D. Jurafsky, J. Chai, N. Schluter, and J. Tetreault, editors, Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 5185–5198, Online, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[12] H. Grice.Logic and conversation.In P. Cole and J. L. Morgan, editors, Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3, Speech Acts, pages 41–58. Academic Press, New York, 1975.

·[13] H. H. Clark.Arenas of Language Use.University of Chicago Press, 1992.

·[14] L. Ouyang, J. Wu, X. Jiang, D. Almeida, C. Wainwright, P. Mishkin, C. Zhang, S. Agarwal, K. Slama, A. Ray, et al.Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback.Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:27730–27744, 2022.

·[15] G. Mialon, R. Dessì, M. Lomeli, C. Nalmpantis, R. Pasunuru, R. Raileanu, B. Rozière, T. Schick, J. Dwivedi-Yu, A. Celikyilmaz, et al.Augmented language models: a survey.arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.07842, 2023.

·[16] M. Halle.Phonology in generative grammar.Word, 18(1-3):54–72, 1962.

·[17] M. Aronoff and K. Fudeman.What is morphology?John Wiley & Sons, 2022.

·[18] D. A. Cruse.Lexical Semantics.Cambridge University Press, 1986.

·[19] M. Dalrymple and T. H. King.An amazing four doctoral dissertations.Argumentum, 15(2019), 2019.Publisher: Debreceni Egyetemi Kiado.

·[20] C. Keenan.A pleasant three days in Philadelphia: Arguments for a pseudopartitive analysis.University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 19(1):11, 2013.

·[21] A. E. Goldberg.Explain me this: Creativity, competition, and the partial productivity of constructions.Princeton University Press, 2019.

·[22] J. Bresnan.Is syntactic knowledge probabilistic? Experiments with the English dative alternation.Roots: Linguistics in search of its evidential base, 96:77–96, 2007.

·[23] A. Clark.Distributional Learning as a Theory of Language Acquisition.In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Cognitive Aspects of Computational Language Learning (CogACLL), page 29, Gothenburg, Sweden, April 2014. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[24] J. Saffran, R. Aslin, and E. Newport.Statistical learning by 8-month-old infants.Science, 274(5294):1926, 1996.

·[25] N. Chomsky.Syntactic Structures.The Hague: Mouton, 1957.

·[26] L. R. Gleitman.A human universal: the capacity to learn a language.Modern Philology, 90:S13–S33, 1993.Publisher: University of Chicago Press.

·[27] R. Jackendoff.Foundations of Language: Brain, meaning, grammar, evolution, 2002.

·[28] H. H. Clark.Using Language.Cambridge university press, 1996.

·[29] M. Bucholtz and K. Hall.Language and identity.A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology, 1:369–394, 2004.

·[30] F. Deniz, A. O. Nunez-Elizalde, A. G. Huth, and J. L. Gallant.The Representation of Semantic Information Across Human Cerebral Cortex During Listening Versus Reading Is Invariant to Stimulus Modality.Journal of Neuroscience, 39(39):7722–7736, September 2019.Publisher: Society for Neuroscience Section: Research Articles.

·[31] E. Fedorenko, P.-J. Hsieh, A. Nieto-Castañón, S. Whitfield-Gabrieli, and N. Kanwisher.New method for fMRI investigations of language: defining ROIs functionally in individual subjects.Journal of Neurophysiology, 104(2):1177–1194, August 2010.

·[32] M. MacSweeney, B. Woll, R. Campbell, P. K. McGuire, A. S. David, S. C. R. Williams, J. Suckling, G. A. Calvert, and M. J. Brammer.Neural systems underlying British Sign Language and audio-visual English processing in native users.Brain, 125(7):1583–1593, July 2002.

·[33] T. L. Scott, J. Gallée, and E. Fedorenko.A new fun and robust version of an fMRI localizer for the frontotemporal language system.Cognitive Neuroscience, 8(3):167–176, 2017.

·[34] L. Menenti, S. M. E. Gierhan, K. Segaert, and P. Hagoort.Shared language: overlap and segregation of the neuronal infrastructure for speaking and listening revealed by functional MRI.Psychological Science, 22(9):1173–1182, September 2011.

·[35] J. Hu, H. Small, H. Kean, A. Takahashi, L. Zekelman, D. Kleinman, E. Ryan, A. Nieto-Castañón, V. Ferreira, and E. Fedorenko.Precision fmri reveals that the language-selective network supports both phrase-structure building and lexical access during language production.Cerebral Cortex, 33(8):4384–4404, 2023.

·[36] T. I. Regev, J. Affourtit, X. Chen, A. E. Schipper, L. Bergen, K. Mahowald, and E. Fedorenko.High-level language brain regions are sensitive to sub-lexical regularities.bioRxiv, 2021.

·[37] E. Fedorenko, M. K. Behr, and N. Kanwisher.Functional specificity for high-level linguistic processing in the human brain.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(39):16428–16433, September 2011.

·[38] E. Fedorenko, I. A. Blank, M. Siegelman, and Z. Mineroff.Lack of selectivity for syntax relative to word meanings throughout the language network.Cognition, 203:104348, October 2020.

·[39] E. Bates, S. M. Wilson, A. P. Saygin, F. Dick, M. I. Sereno, R. T. Knight, and N. F. Dronkers.Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping.Nature Neuroscience, 6(5):448–450, May 2003.

·[40] S. M. Wilson, D. K. Eriksson, M. Yen, A. T. Demarco, S. M. Schneck, and J. M. Lucanie.Language Mapping in Aphasia.Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research : JSLHR, 62(11):3937–3946, November 2019.

·[41] M. Amalric and S. Dehaene.Origins of the brain networks for advanced mathematics in expert mathematicians.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(18):4909–4917, May 2016.

·[42] Y. Benn, A. A. Ivanova, O. Clark, Z. Mineroff, C. Seikus, J. S. Silva, R. Varley, and E. Fedorenko.The language network is not engaged in object categorization.Cerebral Cortex, 33(19):10380–10400, 2023.

·[43] X. Chen, J. Affourtit, R. Ryskin, T. I. Regev, S. Norman-Haignere, O. Jouravlev, S. Malik-Moraleda, H. Kean, R. Varley, and E. Fedorenko.The human language system, including its inferior frontal component in “Broca’s area,” does not support music perception.Cerebral Cortex, 33(12):7904–7929, 04 2023.

·[44] B. Deen, K. Koldewyn, N. Kanwisher, and R. Saxe.Functional Organization of Social Perception and Cognition in the Superior Temporal Sulcus.Cerebral Cortex, 25(11):4596–4609, November 2015.

·[45] O. Jouravlev, D. Zheng, Z. Balewski, A. L. A. Pongos, Z. Levan, S. Goldin-Meadow, and E. Fedorenko.Speech-accompanying gestures are not processed by the language-processing mechanisms.Neuropsychologia, 132:107132, September 2019.

·[46] Y.-F. Liu, J. Kim, C. Wilson, and M. Bedny.Computer code comprehension shares neural resources with formal logical inference in the fronto-parietal network.eLife, 9:e59340, dec 2020.

·[47] M. M. Monti, L. M. Parsons, and D. N. Osherson.Thought beyond language: neural dissociation of algebra and natural language.Psychological Science, 23(8):914–922, August 2012.

·[48] A. M. Paunov, I. A. Blank, O. Jouravlev, Z. Mineroff, J. Gallée, and E. Fedorenko.Differential Tracking of Linguistic vs. Mental State Content in Naturalistic Stimuli by Language and Theory of Mind (ToM) Brain Networks.Neurobiology of Language, pages 1–29, June 2022.

·[49] E. Fedorenko and R. A. Varley.Language and thought are not the same thing: evidence from neuroimaging and neurological patients: Language versus thought.Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369(1):132–153, April 2016.

·[50] L. Fridman.Noam Chomsky: Language, Cognition, and Deep Learning: Lex Fridman Podcast #53.Available online, 2019.Accessed: January 1, 2024.

·[51] T. Linzen.What can linguistics and deep learning contribute to each other? Response to Pater.Language, 95(1):e99–e108, 2019.Publisher: Linguistic Society of America.

·[52] I. A. Blank.What are large language models supposed to model?Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2023.

·[53] S. Jain, V. A. Vo, L. Wehbe, and A. G. Huth.Computational language modeling and the promise of in silico experimentation.Neurobiology of Language, pages 1–65, 2023.

·[54] M. C. Frank.Openly accessible LLMs can help us to understand human cognition.Nature Human Behaviour, pages 1–3, 2023.

·[55] R. Cao and D. Yamins.Explanatory models in neuroscience: Part 1–taking mechanistic abstraction seriously.arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.01490, 2021.

·[56] M. Baroni.On the proper role of linguistically-oriented deep net analysis in linguistic theorizing.Algebraic structures in natural language, pages 1–16, 2022.

·[57] D. Jurafsky and J. H. Martin.Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition.Pearson Prentice Hall, second edition, 2009.

·[58] M. Baroni and A. Lenci.Distributional memory: A general framework for corpus-based semantics.Computational Linguistics, 36(4):673–721, 2010.

·[59] K. Erk.Vector space models of word meaning and phrase meaning: A survey.Language and Linguistics Compass, 6(10):635–653, 2012.

·[60] D. E. Rumelhart and J. L. McClelland.Parallel Distributed Processing.MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1986.

·[61] J. Elman.Learning and development in neural networks: the importance of starting small.Cognition, 48(1):71–99, 1993.

·[62] P. Norvig.Colorless green ideas learn furiously: Chomsky and the two cultures of statistical learning.Significance, 9(4):30–33, 2012.

·[63] S. Pinker and A. Prince.On language and connectionism: Analysis of a parallel distributed processing model of language acquisition.Cognition, 28(1-2):73–193, 1988.Publisher: Elsevier.

·[64] M. B. Everaert, M. A. Huybregts, N. Chomsky, R. C. Berwick, and J. J. Bolhuis.Structures, not strings: linguistics as part of the cognitive sciences.Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(12):729–743, 2015.

·[65] R. Sennrich, B. Haddow, and A. Birch.Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units.In K. Erk and N. A. Smith, editors, Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 1715–1725, Berlin, Germany, August 2016. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[66] S. Bowman.The dangers of underclaiming: Reasons for caution when reporting how NLP systems fail.In S. Muresan, P. Nakov, and A. Villavicencio, editors, Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 7484–7499, Dublin, Ireland, May 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[67] I. Sutskever, J. Martens, and G. E. Hinton.Generating text with recurrent neural networks.In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-11), pages 1017–1024, 2011.

·[68] A. Radford, J. Wu, R. Child, D. Luan, D. Amodei, and I. Sutskever.Language models are unsupervised multitask learners.OpenAI Blog, 1(8), 2019.

·[69] T. B. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell, S. Agarwal, A. Herbert-Voss, G. Krueger, T. Henighan, R. Child, A. Ramesh, D. M. Ziegler, J. Wu, C. Winter, C. Hesse, M. Chen, E. Sigler, M. Litwin, S. Gray, B. Chess, J. Clark, C. Berner, S. McCandlish, A. Radford, I. Sutskever, and D. Amodei.Language Models are Few-Shot Learners.In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020.

·[70] A. Lenci.Understanding natural language understanding systems. a critical analysis.Sistemi Intelligenti, 35(2):277–302, 2023.

·[71] M. Van Schijndel and T. Linzen.Single-stage prediction models do not explain the magnitude of syntactic disambiguation difficulty.Cognitive Science, 45(6):e12988, 2021.

·[72] G. Beguš.CiwGAN and fiwGAN: Encoding information in acoustic data to model lexical learning with generative adversarial networks.Neural Networks, 139:305–325, 2021.

·[73] R. T. McCoy, P. Smolensky, T. Linzen, J. Gao, and A. Celikyilmaz.How much do language models copy from their training data? evaluating linguistic novelty in text generation using RAVEN.Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 11:652–670, 2023.

·[74] G. Chronis and K. Erk.When is a bishop not like a rook? when it’s like a rabbi! multi-prototype BERT embeddings for estimating semantic relationships.In R. Fernández and T. Linzen, editors, Proceedings of the 24th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, pages 227–244, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[75] A. Wang, A. Singh, J. Michael, F. Hill, O. Levy, and S. R. Bowman.GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark and Analysis Platform for Natural Language Understanding.In Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, pages 353–355, 2018.

·[76] A. Warstadt, A. Parrish, H. Liu, A. Mohananey, W. Peng, S.-F. Wang, and S. R. Bowman.BLiMP: The Benchmark of Linguistic Minimal Pairs for English.Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 8:377–392, 2020.

·[77] D. Samuel.Mean BERTs make erratic language teachers: the effectiveness of latent bootstrapping in low-resource settings.In A. Warstadt, A. Mueller, L. Choshen, E. Wilcox, C. Zhuang, J. Ciro, R. Mosquera, B. Paranjabe, A. Williams, T. Linzen, and R. Cotterell, editors, Proceedings of the BabyLM Challenge at the 27th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, pages 221–237, Singapore, December 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[78] A. Warstadt, A. Mueller, L. Choshen, E. Wilcox, C. Zhuang, J. Ciro, R. Mosquera, B. Paranjabe, A. Williams, T. Linzen, and R. Cotterell.Findings of the BabyLM challenge: Sample-efficient pretraining on developmentally plausible corpora.In A. Warstadt, A. Mueller, L. Choshen, E. Wilcox, C. Zhuang, J. Ciro, R. Mosquera, B. Paranjabe, A. Williams, T. Linzen, and R. Cotterell, editors, Proceedings of the BabyLM Challenge at the 27th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, pages 1–34, Singapore, December 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[79] J. Gauthier, J. Hu, E. Wilcox, P. Qian, and R. Levy.SyntaxGym: An Online Platform for Targeted Evaluation of Language Models.In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, pages 70–76, Online, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[80] T. Linzen, E. Dupoux, and Y. Goldberg.Assessing the ability of LSTMs to learn syntax-sensitive dependencies.Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4:521–535, 2016.

·[81] K. Gulordava, P. Bojanowski, E. Grave, T. Linzen, and M. Baroni.Colorless green recurrent networks dream hierarchically.In M. Walker, H. Ji, and A. Stent, editors, Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), pages 1195–1205, New Orleans, Louisiana, June 2018. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[82] T. Linzen and M. Baroni.Syntactic structure from deep learning.Annual Review of Linguistics, 7:195–212, 2021.

·[83] C. Yu, R. Sie, N. Tedeschi, and L. Bergen.Word frequency does not predict grammatical knowledge in language models.In B. Webber, T. Cohn, Y. He, and Y. Liu, editors, Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 4040–4054, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[84] E. G. Wilcox, R. Futrell, and R. Levy.Using computational models to test syntactic learnability.Linguistic Inquiry, pages 1–88, 2022.

·[85] J. Hewitt and C. D. Manning.A structural probe for finding syntax in word representations.In J. Burstein, C. Doran, and T. Solorio, editors, Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4129–4138, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[86] S. Ravfogel, G. Prasad, T. Linzen, and Y. Goldberg.Counterfactual interventions reveal the causal effect of relative clause representations on agreement prediction.In A. Bisazza and O. Abend, editors, Proceedings of the 25th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, pages 194–209, Online, November 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[87] A. Mueller, Y. Xia, and T. Linzen.Causal analysis of syntactic agreement neurons in multilingual language models.In A. Fokkens and V. Srikumar, editors, Proceedings of the 26th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning (CoNLL), pages 95–109, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Hybrid), December 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[88] Y. Lakretz, G. Kruszewski, T. Desbordes, D. Hupkes, S. Dehaene, and M. Baroni.The emergence of number and syntax units in LSTM language models.In J. Burstein, C. Doran, and T. Solorio, editors, Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 11–20, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[89] B. Ambridge.Against stored abstractions: A radical exemplar model of language acquisition.First Language, 40(5-6):509–559, 2020.

·[90] N. Kim and P. Smolensky.Testing for grammatical category abstraction in neural language models.In A. Ettinger, E. Pavlick, and B. Prickett, editors, Proceedings of the Society for Computation in Linguistics 2021, pages 467–470, Online, February 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[91] N. Kim, T. Linzen, and P. Smolensky.Uncontrolled lexical exposure leads to overestimation of compositional generalization in pretrained models.arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10769, 2022.

·[92] K. Misra, J. Rayz, and A. Ettinger.COMPS: Conceptual minimal pair sentences for testing robust property knowledge and its inheritance in pre-trained language models.In A. Vlachos and I. Augenstein, editors, Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 2928–2949, Dubrovnik, Croatia, May 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[93] A. Ettinger, A. Elgohary, and P. Resnik.Probing for semantic evidence of composition by means of simple classification tasks.In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Evaluating Vector-Space Representations for NLP, pages 134–139, Berlin, Germany, August 2016. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[94] Y. Belinkov.Probing classifiers: Promises, shortcomings, and advances.Computational Linguistics, 48(1):207–219, March 2022.

·[95] I. Tenney, D. Das, and E. Pavlick.BERT rediscovers the classical NLP pipeline.In A. Korhonen, D. Traum, and L. Màrquez, editors, Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 4593–4601, Florence, Italy, July 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[96] J. Niu, W. Lu, and G. Penn.Does BERT rediscover a classical NLP pipeline?In N. Calzolari, C.-R. Huang, H. Kim, J. Pustejovsky, L. Wanner, K.-S. Choi, P.-M. Ryu, H.-H. Chen, L. Donatelli, H. Ji, S. Kurohashi, P. Paggio, N. Xue, S. Kim, Y. Hahm, Z. He, T. K. Lee, E. Santus, F. Bond, and S.-H. Na, editors, Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 3143–3153, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, October 2022. International Committee on Computational Linguistics.

·[97] M. C. MacDonald, N. J. Pearlmutter, and M. S. Seidenberg.The lexical nature of syntactic ambiguity resolution.Psychological Review, 101(4):676, 1994.Publisher: American Psychological Association.

·[98] E. Bates and B. MacWhinney.Functionalism and the competition model.In B. MacWhinney and E. Bates, editors, The Crosslinguistic Study of Sentence Processing, pages 3–73. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

·[99] I. Dasgupta, A. K. Lampinen, S. C. Chan, A. Creswell, D. Kumaran, J. L. McClelland, and F. Hill.Language models show human-like content effects on reasoning.arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.07051, 2022.

·[100] A. K. Lampinen.Can language models handle recursively nested grammatical structures? a case study on comparing models and humans.arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.15303, 2022.

·[101] Y. Lakretz, T. Desbordes, D. Hupkes, and S. Dehaene.Causal Transformers Perform Below Chance on Recursive Nested Constructions, Unlike Humans, October 2021.arXiv:2110.07240 [cs].

·[102] L. Weissweiler, T. He, N. Otani, D. R. Mortensen, L. Levin, and H. Schütze.Construction grammar provides unique insight into neural language models.In C. Bonial and H. Tayyar Madabushi, editors, Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Construction Grammars and NLP (CxGs+NLP, GURT/SyntaxFest 2023), pages 85–95, Washington, D.C., March 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[103] Y.-H. Tseng, C.-F. Shih, P.-E. Chen, H.-Y. Chou, M.-C. Ku, and S.-K. Hsieh.CxLM: A construction and context-aware language model.In N. Calzolari, F. Béchet, P. Blache, K. Choukri, C. Cieri, T. Declerck, S. Goggi, H. Isahara, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, H. Mazo, J. Odijk, and S. Piperidis, editors, Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, pages 6361–6369, Marseille, France, June 2022. European Language Resources Association.

·[104] H. Tayyar Madabushi, L. Romain, D. Divjak, and P. Milin.CxGBERT: BERT meets construction grammar.In D. Scott, N. Bel, and C. Zong, editors, Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 4020–4032, Barcelona, Spain (Online), December 2020. International Committee on Computational Linguistics.

·[105] K. Mahowald.A discerning several thousand judgments: GPT-3 rates the article + adjective + numeral + noun construction.In A. Vlachos and I. Augenstein, editors, Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 265–273, Dubrovnik, Croatia, May 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[106] C. Potts.Characterizing English Preposing in PP constructions.LingBuzz, 2023.lingbuzz/007495.

·[107] L. Weissweiler, V. Hofmann, A. Köksal, and H. Schütze.The better your syntax, the better your semantics? probing pretrained language models for the English comparative correlative.In Y. Goldberg, Z. Kozareva, and Y. Zhang, editors, Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 10859–10882, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, December 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[108] E. Fedorenko, T. L. Scott, P. Brunner, W. G. Coon, B. Pritchett, G. Schalk, and N. Kanwisher.Neural correlate of the construction of sentence meaning.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(41):E6256–E6262, October 2016.Publisher: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

·[109] C. Pallier, A.-D. Devauchelle, and S. Dehaene.Cortical representation of the constituent structure of sentences.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(6):2522–2527, February 2011.Publisher: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

·[110] R. Law and L. Pylkkänen.Lists with and without syntax: A new approach to measuring the neural processing of syntax.Journal of Neuroscience, January 2021.Publisher: Society for Neuroscience Section: Research Articles.

·[111] C. Shain, I. A. Blank, M. van Schijndel, W. Schuler, and E. Fedorenko.fMRI reveals language-specific predictive coding during naturalistic sentence comprehension.Neuropsychologia, 138:107307, 2020.

·[112] J. R. Brennan, C. Dyer, A. Kuncoro, and J. T. Hale.Localizing syntactic predictions using recurrent neural network grammars.Neuropsychologia, 146:107479, September 2020.

·[113] M. Heilbron, K. Armeni, J.-M. Schoffelen, P. Hagoort, and F. P. de Lange.A hierarchy of linguistic predictions during natural language comprehension.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(32):e2201968119, August 2022.Publisher: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

·[114] A. J. Reddy and L. Wehbe.Can fMRI reveal the representation of syntactic structure in the brain?In M. Ranzato, A. Beygelzimer, Y. Dauphin, P. S. Liang, and J. W. Vaughan, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 34, pages 9843–9856. Curran Associates, Inc., 2021.

·[115] J. Y. Huang, K.-H. Huang, and K.-W. Chang.Disentangling semantics and syntax in sentence embeddings with pre-trained language models.In K. Toutanova, A. Rumshisky, L. Zettlemoyer, D. Hakkani-Tur, I. Beltagy, S. Bethard, R. Cotterell, T. Chakraborty, and Y. Zhou, editors, Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pages 1372–1379, Online, June 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[116] C. Caucheteux and J.-R. King.Brains and algorithms partially converge in natural language processing.Communications Biology, 5(1):1–10, February 2022.Number: 1 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

·[117] A. Goldstein, Z. Zada, E. Buchnik, M. Schain, A. Price, B. Aubrey, S. A. Nastase, A. Feder, D. Emanuel, A. Cohen, A. Jansen, H. Gazula, G. Choe, A. Rao, C. Kim, C. Casto, L. Fanda, W. Doyle, D. Friedman, P. Dugan, L. Melloni, R. Reichart, S. Devore, A. Flinker, L. Hasenfratz, O. Levy, A. Hassidim, M. Brenner, Y. Matias, K. A. Norman, O. Devinsky, and U. Hasson.Shared computational principles for language processing in humans and deep language models.Nature Neuroscience, 25(3):369–380, March 2022.Number: 3 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

·[118] M. Schrimpf, I. A. Blank, G. Tuckute, C. Kauf, E. A. Hosseini, N. Kanwisher, J. B. Tenenbaum, and E. Fedorenko.The neural architecture of language: Integrative modeling converges on predictive processing.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(45), November 2021.Publisher: National Academy of Sciences Section: Biological Sciences.

·[119] E. J. Michaud, Z. Liu, U. Girit, and M. Tegmark.The quantization model of neural scaling.Proceedings of the NeurIPS Conference, 2023.

·[120] S. T. Piantadosi.Modern language models refute Chomsky’s approach to language.Lingbuzz Preprint, lingbuzz/007180, 2023.

·[121] N. Chomsky.Linguistics and cognitive science: problems and mysteries.In The Chomskyan Turn. Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 1991.

·[122] T. McCoy, E. Pavlick, and T. Linzen.Right for the wrong reasons: Diagnosing syntactic heuristics in natural language inference.In A. Korhonen, D. Traum, and L. Màrquez, editors, Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 3428–3448, Florence, Italy, July 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[123] R. T. McCoy, S. Yao, D. Friedman, M. Hardy, and T. L. Griffiths.Embers of autoregression: Understanding large language models through the problem they are trained to solve.arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.13638, 2023.

·[124] N. Kassner and H. Schütze.Negated and misprimed probes for pretrained language models: Birds can talk, but cannot fly.In D. Jurafsky, J. Chai, N. Schluter, and J. Tetreault, editors, Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 7811–7818, Online, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[125] A. Warstadt and S. R. Bowman.What artificial neural networks can tell us about human language acquisition.Algebraic Structures in Natural Language, pages 17–60, 2022.

·[126] M. van Schijndel, A. Mueller, and T. Linzen.Quantity doesn’t buy quality syntax with neural language models.In K. Inui, J. Jiang, V. Ng, and X. Wan, editors, Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), pages 5831–5837, Hong Kong, China, November 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[127] R. T. McCoy, R. Frank, and T. Linzen.Does syntax need to grow on trees? sources of hierarchical inductive bias in sequence-to-sequence networks.Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 8:125–140, 2020.

·[128] A. Yedetore, T. Linzen, R. Frank, and R. T. McCoy.How poor is the stimulus? evaluating hierarchical generalization in neural networks trained on child-directed speech.In A. Rogers, J. Boyd-Graber, and N. Okazaki, editors, Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 9370–9393, Toronto, Canada, July 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[129] L. Georges Gabriel Charpentier and D. Samuel.Not all layers are equally as important: Every layer counts BERT.In A. Warstadt, A. Mueller, L. Choshen, E. Wilcox, C. Zhuang, J. Ciro, R. Mosquera, B. Paranjabe, A. Williams, T. Linzen, and R. Cotterell, editors, Proceedings of the BabyLM Challenge at the 27th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, pages 238–252, Singapore, December 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[130] E. A. Hosseini, M. Schrimpf, Y. Zhang, S. R. Bowman, N. Zaslavsky, and E. Fedorenko.Artificial neural network language models predict human brain responses to language even after a developmentally realistic amount of training.Neurobiology of Language, pages 1–50, 01 2024.

·[131] D. Blasi, A. Anastasopoulos, and G. Neubig.Systematic inequalities in language technology performance across the world’s languages.In S. Muresan, P. Nakov, and A. Villavicencio, editors, Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5486–5505, Dublin, Ireland, May 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[132] S. J. Mielke, R. Cotterell, K. Gorman, B. Roark, and J. Eisner.What kind of language is hard to language-model?In A. Korhonen, D. Traum, and L. Màrquez, editors, Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 4975–4989, Florence, Italy, July 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[133] L. Martin, B. Muller, P. J. Ortiz Suárez, Y. Dupont, L. Romary, É. de la Clergerie, D. Seddah, and B. Sagot.CamemBERT: a tasty French language model.In D. Jurafsky, J. Chai, N. Schluter, and J. Tetreault, editors, Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 7203–7219, Online, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[134] Z. Wang, K. K, S. Mayhew, and D. Roth.Extending multilingual BERT to low-resource languages.In T. Cohn, Y. He, and Y. Liu, editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pages 2649–2656, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[135] K. Tirumala, A. Markosyan, L. Zettlemoyer, and A. Aghajanyan.Memorization without overfitting: Analyzing the training dynamics of large language models.Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:38274–38290, 2022.

·[136] D. C. Dennett.The role of language in intelligence.In What is Intelligence? The Darwin College Lectures, ed. Jean Khalfa, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1994.

·[137] P. Carruthers.The cognitive functions of language.The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25(6):657–674; discussion 674–725, December 2002.

·[138] J. Duncan.The multiple-demand (MD) system of the primate brain: mental programs for intelligent behaviour.Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(4):172–179, April 2010.

·[139] J. Fischer, J. G. Mikhael, J. B. Tenenbaum, and N. Kanwisher.Functional neuroanatomy of intuitive physical inference.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(34):E5072–E5081, August 2016.

·[140] A. A. Ivanova, S. Srikant, Y. Sueoka, H. H. Kean, R. Dhamala, U.-M. O’reilly, M. U. Bers, and E. Fedorenko.Comprehension of computer code relies primarily on domain-general executive brain regions.eLife, 9:e58906, 2020.

·[141] A. Woolgar, A. Parr, R. Cusack, R. Thompson, I. Nimmo-Smith, T. Torralva, M. Roca, N. Antoun, F. Manes, and J. Duncan.Fluid intelligence loss linked to restricted regions of damage within frontal and parietal cortex.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(33):14899–14902, August 2010.ISBN: 9781007928108 Publisher: National Academy of Sciences Section: Biological Sciences.

·[142] A. Woolgar, J. Duncan, F. Manes, and E. Fedorenko.Fluid intelligence is supported by the multiple-demand system not the language system.Nature Human Behaviour, 2(3):200–204, 2018.

·[143] N. Dziri, X. Lu, M. Sclar, X. L. Li, L. Jiang, B. Y. Lin, S. Welleck, P. West, C. Bhagavatula, R. L. Bras, J. D. Hwang, S. Sanyal, X. Ren, A. Ettinger, Z. Harchaoui, and Y. Choi.Faith and fate: Limits of transformers on compositionality.In Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023.

·[144] K. Valmeekam, A. Olmo, S. Sreedharan, and S. Kambhampati.Large language models still can’t plan (a benchmark for llms on planning and reasoning about change).In NeurIPS 2022 Foundation Models for Decision Making Workshop, 2022.

·[145] Z. Wu, L. Qiu, A. Ross, E. Akyürek, B. Chen, B. Wang, N. Kim, J. Andreas, and Y. Kim.Reasoning or reciting? exploring the capabilities and limitations of language models through counterfactual tasks.arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.02477, 2023.

·[146] H. Zhang, L. H. Li, T. Meng, K.-W. Chang, and G. Van den Broeck.On the paradox of learning to reason from data.In E. Elkind, editor, Proceedings of the Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-23, pages 3365–3373. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 8 2023.Main Track.

·[147] J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans, M. Bosma, F. Xia, E. Chi, Q. V. Le, D. Zhou, et al.Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models.Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:24824–24837, 2022.

·[148] Wolfram.Wolfram plugin for chatgpt.https://www.wolfram.com/wolfram-plugin-chatgpt/, 2023.Accessed: January 1, 2024.

·[149] L. Wong, G. Grand, A. K. Lew, N. D. Goodman, V. K. Mansinghka, J. Andreas, and J. B. Tenenbaum.From word models to world models: Translating from natural language to the probabilistic language of thought.arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.12672, 2023.

·[150] I. Yildirim and L. Paul.From task structures to world models: What do LLMs know?arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.04276, 2023.

·[151] A. A. Ivanova, Z. Mineroff, V. Zimmerer, N. Kanwisher, R. Varley, and E. Fedorenko.The Language Network is Recruited but Not Required for Nonverbal Event Semantics.Neurobiology of Language, pages 1–26, January 2021.Publisher: MIT Press.

·[152] K. Patterson, P. J. Nestor, and T. T. Rogers.Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain.Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 8(12):976–987, December 2007.

·[153] G. Grand, I. A. Blank, F. Pereira, and E. Fedorenko.Semantic projection recovers rich human knowledge of multiple object features from word embeddings.Nature Human Behaviour, 6(7):975–987, 2022.

·[154] F. Petroni, T. Rocktäschel, S. Riedel, P. Lewis, A. Bakhtin, Y. Wu, and A. Miller.Language Models as Knowledge Bases?In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), pages 2463–2473, Hong Kong, China, November 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[155] N. Liu, T. Zhang, and P. Liang.Evaluating verifiability in generative search engines.In H. Bouamor, J. Pino, and K. Bali, editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, pages 7001–7025, Singapore, December 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[156] M. Sclar, Y. Choi, Y. Tsvetkov, and A. Suhr.Quantifying language models’ sensitivity to spurious features in prompt design or: How I learned to start worrying about prompt formatting.arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.11324, 2023.

·[157] J. Gordon and B. Van Durme.Reporting bias and knowledge acquisition.In Proceedings of the 2013 workshop on Automated knowledge base construction, pages 25–30, 2013.

·[158] X. Liu, D. Yin, Y. Feng, and D. Zhao.Things not written in text: Exploring spatial commonsense from visual signals.In S. Muresan, P. Nakov, and A. Villavicencio, editors, Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2365–2376, Dublin, Ireland, May 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[159] Y. Kim, J. Yoon, S. Ye, S. J. Hwang, and S.-Y. Yun.Carpe diem: On the evaluation of world knowledge in lifelong language models.In NeurIPS 2023 Workshop on Synthetic Data Generation with Generative AI, 2023.

·[160] K. Meng, D. Bau, A. Andonian, and Y. Belinkov.Locating and editing factual associations in gpt.Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:17359–17372, 2022.

·[161] S. Borgeaud, A. Mensch, J. Hoffmann, T. Cai, E. Rutherford, K. Millican, G. B. Van Den Driessche, J.-B. Lespiau, B. Damoc, A. Clark, et al.Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens.In International conference on machine learning, pages 2206–2240. PMLR, 2022.

·[162] R. Cohen, M. Geva, J. Berant, and A. Globerson.Crawling the internal knowledge-base of language models.In A. Vlachos and I. Augenstein, editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2023, pages 1856–1869, Dubrovnik, Croatia, May 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[163] E. Chersoni, E. Santus, L. Pannitto, A. Lenci, P. Blache, and C.-R. Huang.A structured distributional model of sentence meaning and processing.Natural Language Engineering, 25(4):483–502, 2019.

·[164] T. A. Van Dijk and W. Kintsch.Strategies of Discourse Comprehension.Academic Press: New York, 1983.

·[165] Y. Lerner, C. J. Honey, L. J. Silbert, and U. Hasson.Topographic Mapping of a Hierarchy of Temporal Receptive Windows Using a Narrated Story.The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(8):2906–2915, February 2011.

·[166] N. Jacoby and E. Fedorenko.Discourse-level comprehension engages medial frontal Theory of Mind brain regions even for expository texts.Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 35(6):780–796, July 2020.Publisher: Routledge _eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2018.1525494.

·[167] R. L. Buckner and L. M. DiNicola.The brain’s default network: Updated anatomy, physiology and evolving insights.Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 20(10):593–608, 2019.Place: United Kingdom Publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

·[168] C. Baldassano, J. Chen, A. Zadbood, J. W. Pillow, U. Hasson, and K. A. Norman.Discovering Event Structure in Continuous Narrative Perception and Memory.Neuron, 95(3):709–721.e5, August 2017.

·[169] J. Su, M. Ahmed, Y. Lu, S. Pan, W. Bo, and Y. Liu.Roformer: Enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding.Neurocomputing, 568:127063, 2024.

·[170] D. S. Moirangthem and M. Lee.Abstractive summarization of long texts by representing multiple compositionalities with temporal hierarchical pointer generator network.Neural Networks, 124:1–11, 2020.

·[171] Q. Ruan, M. Ostendorff, and G. Rehm.HiStruct+: Improving extractive text summarization with hierarchical structure information.In S. Muresan, P. Nakov, and A. Villavicencio, editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022, pages 1292–1308, Dublin, Ireland, May 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[172] N. Kim and S. Schuster.Entity tracking in language models.In A. Rogers, J. Boyd-Graber, and N. Okazaki, editors, Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 3835–3855, Toronto, Canada, July 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[173] S. Schuster and T. Linzen.When a sentence does not introduce a discourse entity, transformer-based models still sometimes refer to it.In M. Carpuat, M.-C. de Marneffe, and I. V. Meza Ruiz, editors, Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pages 969–982, Seattle, United States, July 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[174] C. Andrés-Roqueta and N. Katsos.The Contribution of Grammar, Vocabulary and Theory of Mind in Pragmatic Language Competence in Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders.Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2017.

·[175] S. Levinson.Presumptive Meanings: The Theory of Generalized Conversational Implicature.MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2000.

·[176] M. Hauptman, I. Blank, and E. Fedorenko.Non-literal language processing is jointly supported by the language and theory of mind networks: Evidence from a novel meta-analytic fmri approach.Cortex, 162:96–114, 2023.

·[177] R. Saxe.Uniquely human social cognition.Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 16(2):235–239, April 2006.

·[178] A. Gopnik and H. M. Wellman.Why the child’s theory of mind really is a theory.Mind and Language, 7(1-2):145–71, 1992.

·[179] R. Saxe and N. Kanwisher.People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in "theory of mind".NeuroImage, 19(4):1835–1842, August 2003.

·[180] N. Jacoby, E. Bruneau, J. Koster-Hale, and R. Saxe.Localizing Pain Matrix and Theory of Mind networks with both verbal and non-verbal stimuli.NeuroImage, 126:39–48, February 2016.

·[181] E. C. Ferstl and D. Y. von Cramon.What Does the Frontomedian Cortex Contribute to Language Processing: Coherence or Theory of Mind?NeuroImage, 17(3):1599–1612, November 2002.

·[182] R. Saxe and L. J. Powell.It’s the thought that counts: specific brain regions for one component of theory of mind.Psychological Science, 17(8):692–699, August 2006.

·[183] P. Hagoort and S. C. Levinson.Neuropragmatics.In The cognitive neurosciences, 5th ed, pages 667–674. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, US, 2014.

·[184] J. Hu, S. Floyd, O. Jouravlev, E. Fedorenko, and E. Gibson.A fine-grained comparison of pragmatic language understanding in humans and language models.In A. Rogers, J. Boyd-Graber, and N. Okazaki, editors, Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4194–4213, Toronto, Canada, July 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[185] M. Kosinski.Theory of mind may have spontaneously emerged in large language models.arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02083, 2023.

·[186] T. Ullman.Large language models fail on trivial alterations to theory-of-mind tasks.arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.08399, 2023.

·[187] N. Shapira, M. Levy, S. H. Alavi, X. Zhou, Y. Choi, Y. Goldberg, M. Sap, and V. Shwartz.Clever hans or neural theory of mind? stress testing social reasoning in large language models.arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14763, 2023.

·[188] M. Sap, R. Le Bras, D. Fried, and Y. Choi.Neural theory-of-mind? on the limits of social intelligence in large LMs.In Y. Goldberg, Z. Kozareva, and Y. Zhang, editors, Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 3762–3780, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, December 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[189] S. Trott, C. Jones, T. Chang, J. Michaelov, and B. Bergen.Do large language models know what humans know?Cognitive Science, 47(7):e13309, 2023.

·[190] K. Gandhi, J.-P. Fränken, T. Gerstenberg, and N. Goodman.Understanding social reasoning in language models with language models.In Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track, 2023.

·[191] M. Sclar, S. Kumar, P. West, A. Suhr, Y. Choi, and Y. Tsvetkov.Minding language models’ (lack of) theory of mind: A plug-and-play multi-character belief tracker.In A. Rogers, J. Boyd-Graber, and N. Okazaki, editors, Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 13960–13980, Toronto, Canada, July 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[192] S. R. Waxman.Early word-learning and conceptual development: Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a new thought.Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development, pages 102–126, 2002.

·[193] J. E. Pyers and A. Senghas.Language promotes false-belief understanding: Evidence from learners of a new sign language.Psychological science, 20(7):805–812, 2009.

·[194] B. Pitt, E. Gibson, and S. T. Piantadosi.Exact number concepts are limited to the verbal count range.Psychological Science, 33(3):371–381, 2022.

·[195] L. Bottou and P. Gallinari.A framework for the cooperation of learning algorithms.Advances in neural information processing systems, 3, 1990.

·[196] E. Ronco and P. J. Gawthrop.Neural networks for modelling and control.Rapport Technique csc, 97008, 1997.

·[197] Q. Liu, D. Yogatama, and P. Blunsom.Relational Memory-Augmented Language Models.Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 10:555–572, May 2022.

·[198] J. Mao, C. Gan, P. Kohli, J. B. Tenenbaum, and J. Wu.The neuro-symbolic concept learner: Interpreting scenes, words, and sentences from natural supervision.In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019.

·[199] D. Hudson and C. D. Manning.Learning by abstraction: The neural state machine.In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 5901–5914, 2019.

·[200] T. Schick, J. Dwivedi-Yu, R. Dessì, R. Raileanu, M. Lomeli, L. Zettlemoyer, N. Cancedda, and T. Scialom.Toolformer: Language models can teach themselves to use tools.arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.04761, 2023.

·[201] K. Cobbe, V. Kosaraju, M. Bavarian, M. Chen, H. Jun, L. Kaiser, M. Plappert, J. Tworek, J. Hilton, R. Nakano, et al.Training verifiers to solve math word problems.arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168, 2021.

·[202] B. Liu, Y. Jiang, X. Zhang, Q. Liu, S. Zhang, J. Biswas, and P. Stone.LLM+P: Empowering large language models with optimal planning proficiency.arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.11477, 2023.

·[203] G. R. Yang, M. R. Joglekar, H. F. Song, W. T. Newsome, and X.-J. Wang.Task representations in neural networks trained to perform many cognitive tasks.Nature Neuroscience, 22(2):297–306, February 2019.Number: 2 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

·[204] K. Dobs, J. Martinez, A. J. E. Kell, and N. Kanwisher.Brain-like functional specialization emerges spontaneously in deep neural networks.Science Advances, 8(11):eabl8913, March 2022.

·[205] C. D. Manning, K. Clark, J. Hewitt, U. Khandelwal, and O. Levy.Emergent linguistic structure in artificial neural networks trained by self-supervision.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(48):30046–30054, December 2020.

·[206] A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, \. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin.Attention is All you Need.In I. Guyon, U. V. Luxburg, S. Bengio, H. Wallach, R. Fergus, S. Vishwanathan, and R. Garnett, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, pages 5998–6008. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017.

·[207] J. Vig and Y. Belinkov.Analyzing the structure of attention in a transformer language model.In T. Linzen, G. Chrupała, Y. Belinkov, and D. Hupkes, editors, Proceedings of the 2019 ACL Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, pages 63–76, Florence, Italy, August 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[208] A. Goyal, A. Didolkar, A. Lamb, K. Badola, N. R. Ke, N. Rahaman, J. Binas, C. Blundell, M. Mozer, and Y. Bengio.Coordination among neural modules through a shared global workspace.Proceedings of ICLR, 2022.

·[209] S. Kudugunta, Y. Huang, A. Bapna, M. Krikun, D. Lepikhin, M.-T. Luong, and O. Firat.Beyond distillation: Task-level mixture-of-experts for efficient inference.In M.-F. Moens, X. Huang, L. Specia, and S. W.-t. Yih, editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, pages 3577–3599, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, November 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[210] Y. Zhou, T. Lei, H. Liu, N. Du, Y. Huang, V. Zhao, A. M. Dai, Q. V. Le, J. Laudon, et al.Mixture-of-experts with expert choice routing.Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:7103–7114, 2022.

·[211] K. Sakaguchi, R. Le Bras, C. Bhagavatula, and Y. Choi.Winogrande: An adversarial winograd schema challenge at scale.In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 34, pages 8732–8740, 2020.

·[212] Y. Elazar, H. Zhang, Y. Goldberg, and D. Roth.Back to square one: Artifact detection, training and commonsense disentanglement in the Winograd schema.In M.-F. Moens, X. Huang, L. Specia, and S. W.-t. Yih, editors, Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 10486–10500, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, November 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

·[213] J. Kaplan, S. McCandlish, T. Henighan, T. B. Brown, B. Chess, R. Child, S. Gray, A. Radford, J. Wu, and D. Amodei.Scaling laws for neural language models.arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361, 2020.

·[214] E. Yiu, E. Kosoy, and A. Gopnik.Transmission versus truth, imitation versus innovation: What children can do that large language and language-and-vision models cannot (yet).Perspectives on Psychological Science, page 17456916231201401, 2023.

·[215] H. Lederman and K. Mahowald.Are language models more like libraries or like librarians? Bibliotechnism, the Novel Reference Problem, and the attitudes of LLMs.arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.04854, 2024.

·[216] M. Mitchell and D. C. Krakauer.The debate over understanding in AI’s large language models.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(13):e2215907120, 2023.

·[217] E. Pavlick.Symbols and grounding in large language models.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 381(2251):20220041, 2023.

·[218] D. C. Mollo and R. Millière.The vector grounding problem.arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.01481, 2023.

作者:

Kyle Mahowald* 德克萨斯大学奥斯汀分校 mahowald@utexas.edu

Anna A. Ivanova* 佐治亚理工学院 a.ivanova@gatech.edu

Idan A. Blank,加州大学洛杉矶分校 iblank@psych.ucla.edu

Nancy Kanwisher,麻省理工学院 ngk@mit.edu

Joshua B. Tenenbaum,麻省理工学院 jbt@mit.edu

Evelina Fedorenko 麻省理工学院 evelina9@mit.edu

(* 两位主要作者对这项工作的贡献相同)

编译:王庆法